A Second Helping of Southern Rock, Part 1 of 2

A revival of veteran acts and an explosion of new blood in the '90s threatened to rival Southern Rock's golden era. This week, we look back at the highs of the '70s and the lows of the '80s.

Lynyrd Skynyrd (l-r: Allen Collins, Leon Wilkeson, Gary Rossington, Artimus Pyle, Ronnie Van Zant, Billy Powell ca. 1975

The rise of Southern Rock in the 1970s was supported by a perfect storm of occurrences that peaked with Georgia-born Jimmy Carter’s election to the Presidency in 1976. Still, the nation seemed fascinated with the South for most of the decade. Movies such as Walking Tall, White Lightning (both 1973), Gator (1976), and Smokey and the Bandit (1977) - many of which starred Burt Reynolds - all glorified redneck culture. Meanwhile, on the small screen, creators of The Dukes of Hazzard placed the Confederate battle flag on top of a Dodge Charger the Duke boys christened the “General Lee” while racing through imaginary Hazzard County, GA every Friday night.

Of course, the music business, led by Capricorn Records, also took advantage. Founded in Macon, Georgia in 1969 by Otis Redding’s former manager Phil Walden and Frank Fenter, the legendary label stood as Southern Rock's ground zero. Its roster included the Allman Brothers Band, the Marshall Tucker Band, Elvin Bishop, Wet Willie, Grinderswitch, the Ozark Mountain Daredevils, Sea Level, Cowboy, and the Dixie Dregs. As the decade progressed, southern bands from Black Oak Arkansas, Lynyrd Skynyrd, and the Charlie Daniels Band to the Outlaws, Blackfoot, and Molly Hatchet signed to major labels including MCA, Epic, Arista, and Atlantic/Atco. Skynyrd undoubtedly led the way with street-wise yet rural-based lyrics over a blues-by-way-of-British hard rock attack. Southern Rock enjoyed a golden era of airplay, label signings, and tour receipts as the seventies marched on.

Yet on October 20, 1977, a plane carrying members of Lynyrd Skynyrd and their crew crashed near McComb, Mississippi, killing lead singer Ronnie Van Zant, guitarist Steve Gaines, backing vocalist (and Steve’s sister) Cassie Gaines, assistant road manager Dean Kilpatrick, pilot Walter McCreary, and co-pilot William Gray. The crash could be seen as the beginning of the end of Southern Rock’s heyday, even as it continued with varying degrees of success for a few more years.

As the 1970s progressed, the rise and success of Outlaw Country offered some spillover fans with Southern Rock, culminating in a compilation of mostly previously released material by Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Jessi Colter, and Tompall Glaser, Wanted: The Outlaws became the first country album to go platinum.

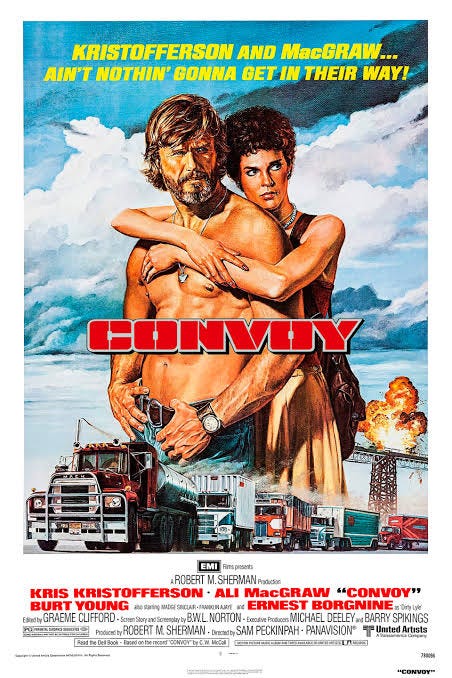

During the Carter administration, as much of the country was still fascinated with the South, Sam Peckinpah unleashed Convoy (1978), a movie starring Kris Kristofferson and Ali McGraw, that capitalized on the CB radio trend that itself had been spurred by C.W. McCall’s number one country and pop hit in 1975.

As the 1980s dawned, however, the nation’s southern cosplay abruptly ended, forcing many Southern rockers to adapt to the changing musical landscape or become obsolete. Some, sadly, did both.

Lost in the Eighties

When Ronald Reagan won the presidency in 1980, carrying all but seven states (even in the South), it appeared America was waking up with a morning-after hangover, looking over its collective shoulder, and regretting what it had done. Before long, CB radios were replaced with a growing fascination with Wall Street; new styles and trends were coming from New York and LA again; the Dukes were traded for Dynasty. The only Southern-adjacent town glorified on ‘80s TV seemed to be Dallas.

With the start of Music Television (MTV) in August of 1981, the music industry pivoted to video. New Wave was the new wave, and the kids coming of age in the ‘80s were much more image-conscious, thanks to MTV’s highly stylized music videos. Some artists fought to stay relevant in this new world while others bowed out completely, either of their own free will or otherwise.

Southern Rock bands appeared to be hit hardest of all. By 1979, Capricorn Records went bankrupt, causing many of their artists to search for new homes. The Dixie Dregs, one of Southern Rock’s more inventive groups with their fusion of country, rock, and jazz, followed the Outlaws to Arista. As a sign of the times, they dropped the “Dixie” from their name in a subtle, yet unsuccessful, bid at commercialism.

After the plane crash, most of the surviving members of Lynyrd Skynyrd reconvened under the umbrella of the Rossington-Collins Band, named after Skynyrd guitarists Gary Rossington and Allen Collins.

RCB’s lead vocalist, Dale Krantz (who would marry Gary Rossington in 1982), was discovered while working as a backup singer for 38 Special. RCB had a rock radio hit with “Don’t Misunderstand Me” in 1979 but were unable to capitalize on it, at least radio-wise.

Meanwhile, 38 Special had spent the seventies rockin’ into the night while in the shadow of Skynyrd. Both bands were closely linked, as vocalist Donnie Van Zant was Ronnie’s younger brother and Larry Junstrom had been Skynyrd’s original bassist. Ironically, 38 Special’s self-titled first album came out just months before Skynyrd’s plane went down. They would release two more albums in the seventies: Special Delivery in ‘78 and Rockin’ into the Night the following year, both trading in the by-then-expected sound and tropes of Southern Rock.

Yet just as Southern Rock was falling out of fashion as the eighties began, 38 Special, who’d been called “Lynyrd Skynyrd, Jr.” when they started, became the group that most successfully navigated the change from redneck rockers to pop/rock hitmakers when Donnie Van Zant urged Don Barnes, who was gifted with the more powerful and melodic voice, to take over lead vocals. The result was a run of FM hits that blended seamlessly with REO Speedwagon, Journey, Toto, Styx, and Foreigner across the airwaves.

Other acts didn’t fare as well.

The Marshall Tucker Band, after the shuttering of Capricorn, moved to Warner Bros, but in April of 1980, bassist Tommy Caldwell died after injuries sustained in a car accident. After a few futile attempts of the surviving members carrying on, by 1984 only Doug Gray and Jerry Eubanks remained from the original lineup.

Molly Hatchet, whose debut came out in 1978, had started as a high-octane Florida boogie machine. Danny Joe Brown’s vocals growled over another three-guitar army: Duane Roland, Steve Holland, and Dave Hlubek. After two LPs, Brown was replaced by the more forceful, but less expressive, Jimmy Farrar who wailed on a pair of albums before Brown rejoined for No Guts, No Glory in 1983.

Then came 1985’s The Deed Is Done.

On the strength of the first single and video, “Satisfied Man”, The Deed Is Done went full throttle ‘80s. (It was also the first Hatchet album not produced by Tom Werman; Terry Manning took the reins instead.) In retrospect, the video to “Satisfied Man” resembles an SNL parody, and, oh my goodness, those keyboard stabs…and that bridge! Still, the song rocks despite itself. And hey, it got them booked on Solid Gold. Molly Hatchet on Solid Gold? That’s the eighties, baby.

Then there’s the case of Blackfoot. In 1979, they delivered a true Southern Rock classic with Strikes, fueled by the undeniable “Train Train” and “Highway Song.” Yet by 1983, we were subjected to “Teenage Idol.”

In 1986, Henry Paul returned to the Outlaws for the first time since ‘77, rejoining Hughie Thomasson to deliver Soldiers of Fortune. It didn’t sell well, but it had its moments, like the title track, the album-closing “Racing for the Red Light,” and, especially, the atmospheric opening track, “One Last Ride.” (About seven years later, Paul would hit gold for a spell with country trio BlackHawk, one of the high points of ‘90s country.)

Meanwhile, the Allman Brothers Band took the high road. Instead of trying to compete with Duran Duran, Michael Jackson, Prince, and Madonna, they just called it quits. If the Gregg Allman Band’s “Evidence of Love” (with Don Johnson) was any indication of what the ABB would’ve sounded like in the mid-’80s, we’re all better off they sat the decade out.

OK, I admit I’m being a little unfair. There were a few good moments on I’m No Angel, especially the title track, even though 1988’s When the Bullets Fly is far superior. Still, “Evidence” is easily the nadir of Gregg’s solo career - and I’m counting Allman and Woman.

The New South

Meanwhile, as veteran Southern rockers were trying - mostly unsuccessfully - to find their footing in the eighties, younger Southern bands were redefining another New South, both in sound and attitude. Groups from Georgia - namely Athens - such as R.E.M., Pylon, and the B-52s led the way with progressive ideals, murky and quirky lyrics, and music influenced by everything from punk, new wave, country, folk, and power-pop. Gators, whiskey, and macho posturing gave way to songs about gardening at night, reptiles, and rock lobsters. Hyper-testosterone-fueled bravado gave way to idiosyncratic ambiguity. (By comparison, and with few exceptions, there had been a severe lack of quirk in ‘70s classic rock.)

Simultaneously, the plastic synth sounds and drum machines were becoming much too commonplace by the middle of the eighties, which led many to reach back for more of an organic, rock’n’roll vibe, albeit with a more modern, punk slant. Hence southern bands from Jason and the (Nashville) Scorchers to Austin’s True Believers and Atlanta’s Georgia Satellites started to experience either commercial success or critical acclaim - sometimes both.

Then there’s the case of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. Although geographically a southern band out of Gainesville, Florida, they were most definitely not Southern Rock. They associated themselves more with the California folk-country-rock sound from the Byrds to the Burritos. However, in 1985, Petty decided to revisit his southern roots with the album Southern Accents.

The original idea, a cycle of character sketches of southerners mixed with a handful of choice covers of country, rockabilly, and southern soul deep cuts, was jettisoned when the Eurythmics’ Dave Stewart got involved. Tracks like “Trailer” were sent to B-side-land in favor of the psychedelia of “Don’t Come Around Here No More.” (“Trailer” was re-recorded later by Petty’s pre-Heartbreakers’ group Mudcrutch for Mudcrutch 2, which also stands as the last Petty album released during his lifetime.)

Some songs remained from the original concept, including the ironically anthemic album opener, “Rebels,” and the classic, moving title track.

The tour supporting Southern Accents was documented on the double album, Pack Up the Plantation LIVE!, the inside gatefold of which boasted a shot of the stage, including as its backdrop a huge Confederate battle flag.

So, I suppose now is as good a time as any to address that damn flag.

Throughout the 1970s and into the ‘80s, the Confederate flag flew at concerts, hung behind bands on stages, and was glorified on tour programs and merchandise sold at shows and in parking lots. On TV, it was painted across the top of the General Lee and was used whenever Hollywood wanted to illustrate a certain part of the South … or a certain kind of Southerner.

For many Gen X’ers and younger Baby Boomers who came of age during the 1970s, we were sold a bill of goods by marketing execs who used the Confederate flag as a way to represent the South in general. In my school, several Black kids as well as white kids watched the Dukes of Hazzard while rooting for Bo and Luke to outrun Sheriff Coltrane and outsmart Boss Hogg every week. Matchbox sold toy General Lee’s (complete with the flag) in department stores nationwide.

Then there were the Southern Rockers, namely Lynyrd Skynyrd, who used the flag as their backdrop when they trotted out “Sweet Home Alabama.” Speaking of Alabama, the Southern Rock-lite country superstars that hit big at the dawn of the 1980s, and shared their home state’s name, had the Rebel flag emblazoned on four of their first five album covers (they’ve all since been redesigned with the Alabama state flag, which logically makes much more sense).

It was a somewhat condescending and very ill-advised marketing tool used by everyone from Hollywood to Madison Avenue. Again, it was used as lazy shorthand for the South, not as a racist dog whistle. (Do we really think Johnny Cash would have agreed to this with nefarious intent?)

Many of us were too young to understand the darkness and evil that the Confederate flag represented. Looking back, I’m embarrassed at how I accepted the flag as an overall symbol of Southern identity, never taking time to consider what it symbolized to the Black kids I went to school with or their especially parents. As we all grew older, and as time (and we) progressed, it’s shameful that a symbol of the “Lost Cause” was celebrated by so many of us, ignorant or otherwise. Tom Petty later regretted the use of Confederate iconography, while acts such as the Allman Brothers never approved the use of such in their marketing. Wisdom, humility, and empathy are powerful antidotes to stubbornness and hate.

Back Where it All Begins

As the decade advanced, old-school southern rockers crept slowly back into the public consciousness. In 1987, the same year Gregg Allman told us he was no angel, the surviving members of Lynyrd Skynyrd were mounting a 10th-deathversary-of-the-crash tour across the US, underlining it with a new album of early outtakes called Legend. Ronnie and Donnie’s youngest brother, Johnny, stepped in as lead singer, and they brought Ed King back into the fold. (Allen Collins was confined to a wheelchair due to an automobile accident that also took the life of his girlfriend, making “That Smell” - originally written with Gary Rossington in mind - all the more prophetic. Collins died of pneumonia on January 23, 1990, almost four years to the day after the accident.)

For the tour, the group billed themselves as “The Lynyrd Skynyrd Tribute Band” under the assumption that this was a one-time thing; a celebration of the legacy of not only Ronnie and the others who perished ten years earlier but of Southern Rock’s glory days. Gary and Dale’s band, Rossington (or The Rossington Band - the two albums they released in the mid-’80s couldn’t decide on a name), opened many of the shows. “Free Bird” was performed as an instrumental with Ronnie’s hat on the mic stand.

Performances from the tour were recorded and released as the live album, Southern by the Grace of God and as a VHS documentary from Cabin Fever Entertainment in 1988. Longtime friend of the band, Charlie Daniels, narrated the doc. (Just a warning before you proceed, this doc does show that damn flag in several shots.)

A year and change after Skynyrd released Southern by the Grace of God, the Allman Brothers Band was given the box set treatment with the help of archival producer extraordinaire, Bill Levenson. Dreams, released in June of 1989, capitalized on the then-box set craze by compiling not only previously unreleased Allmans tracks (as well as lesser-known deep cuts with rock radio classics) but also solo cuts and songs from their pre-Allmans days. (The set was modeled on Eric Clapton’s Crossroads box from the previous year, also overseen by Levenson.)

Dreams not only collected the past but also (unknowingly at the time) predicted the future and arguably set in motion what became Southern Rock’s second wind.

An unexpected success, Dreams even brought the Brothers back together. In addition to the core surviving original lineup of Gregg Allman, Dickey Betts, Jaimoe, and Butch Trucks, they added bassist Allen Woody (from Skynyrd drummer Artimus Pyle’s band, the APB), keyboardist Johnny Neel, and guitarist Warren Haynes (both from Dickey’s band). After a successful summer jaunt, they had so much fun they decided it was a good idea to work up some new material. After signing with Epic and bringing back producer Tom Dowd, Seven Turns was born. Released in July of 1990, it proved the Allmans were truly back in the saddle.

Seven Turns was not the only album by a Southern Rock legacy act in 1990. The year also saw the release of The Marshall Tucker Band’s Southern Spirit.

When Doug Gray and Jerry Eubanks delivered Still Holdin’ On under the MTB moniker a couple of years earlier, frankly, it was a damn mess. Trying too hard to have a country hit with Nashville session players was a sad thing to hear. The production was thin, the songs and performances thinner. For Southern Spirit, they skedaddled back home to South Carolina, recruited some homegrown boys, and delivered an album that could stand proudly alongside their ‘70s peak. Its lead-off track even got some decent rock radio airplay.

Meanwhile, ‘The Lynyrd Skynyrd Tribute’ tour was, predictably, a rousing success, causing its members to contemplate putting out new material as well. Johnny Van Zant’s stature within the group was boosted by his rock radio hit that acted as an ode to his big brother, “Brickyard Road,” which hit in 1990.

With original members Rossington, Powell, Wilkeson, and King, Lynyrd Skynyrd’s new incarnation was flanked by guitarist Randall Hall (who’d played with the Allen Collins Band in the early 1980s), drummer Kurt Custer (a veteran of Night Ranger, the Romantics, and - the biggest news for Southern Rock fans - the drummer on Steve Earle’s Copperhead Road), and, of course, little brother Johnny Van Zant. Hearing what Tom Dowd had accomplished with the Allmans, Skynyrd enlisted him to helm Lynyrd Skynyrd 1991.

However, there’s a marked difference between Allmans’ ‘90s material and Skynyrd’s. Where Seven Turns, Shades of Two Worlds, and Where It All Begins - all released between 1990 and 1994 - found the Allman Brothers Band building on their legacy while maintaining their signature sound, Skynyrd’s output in the ‘90s (1991, The Last Rebel, Endangered Species, Twenty, Edge of Forever) lacked the magic that fueled their ‘70s work. Of course, the ABB still had both Gregg Allman and Dickey Betts guiding them, as well as the inimitable backline of Jaimoe and Butch Trucks. (Their not-so-secret weapon, Warren Haynes, added a soul underpinning that perfectly complimented the vets.) Skynyrd, on the other hand, had lost its guiding creative force. Without Ronnie Van Zant’s deceptively simple observations of the trials and everyday life of the “Simple” Southern Man, Skynyrd in the ‘90s became just another loud rock band that leaned harder into radio-ready/mainstream country music than the original Skynyrd ever did.

“Smokestack Lightning” wasn’t bad; in fact, it was a lot of fun. But it was obvious to everyone that this wasn’t Ronnie’s band anymore. Skynyrd’s lyrics, their most unique component, just became a string of cliches listing Southern tropes and generalizations about country life. The imagination, nuance, and complexities were gone.

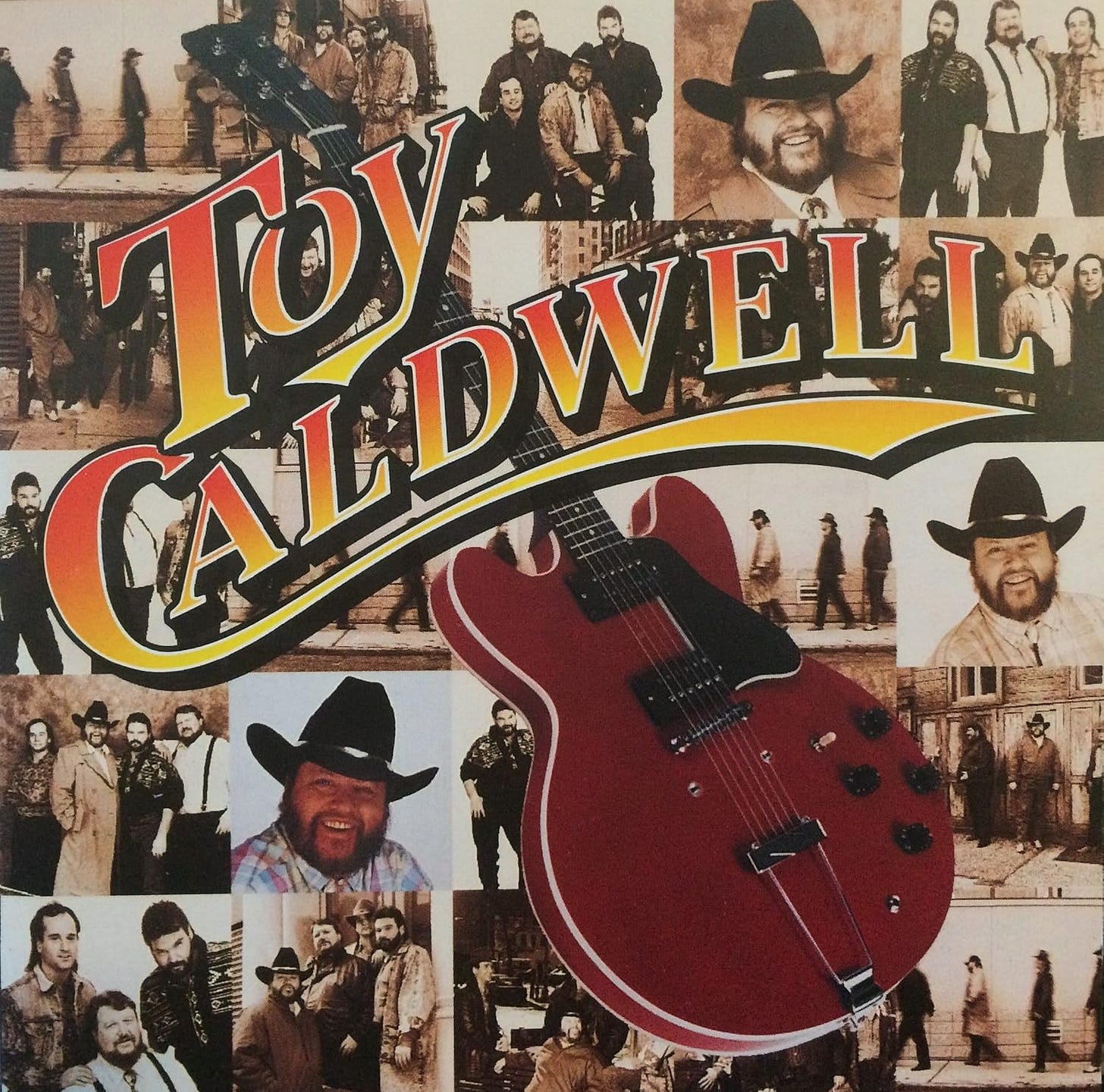

Almost a decade after leaving the Marshall Tucker Band, in 1992, Toy Caldwell released his self-titled debut solo album on the Cabin Fever label (the company that had put out that Skynyrd reunion doc in ‘88).

Although his voice, guitar, and songwriting had been missed on the otherwise pretty-damn-good Southern Spirit, his solo album more than makes up for it. It was obvious he was enjoying himself, and if nothing else, the album gave us one of the great latter-day Southern Rock gems in “Midnight Promises”, a duet with Gregg Allman that, if it had been released 15 years earlier, would now be considered a classic.

Although several key artists of the first wave of Southern Rockers were back in the business of packing arenas and summer sheds, with some releasing music that rivaled their own classic material, it was the new breed that was about to set a new standard - and broaden the scope - of what rock bands that just happen to be Southern could do.

More on that next time.

Excellent post, so much detail! And astute observations of how music changed going into the 1980s, and why. I look forward to diving into the playlist - I'm a big ABB & Skynyrd fan, but have only passing familiarity with most of the other artists there. Thank you.

Outstanding article!