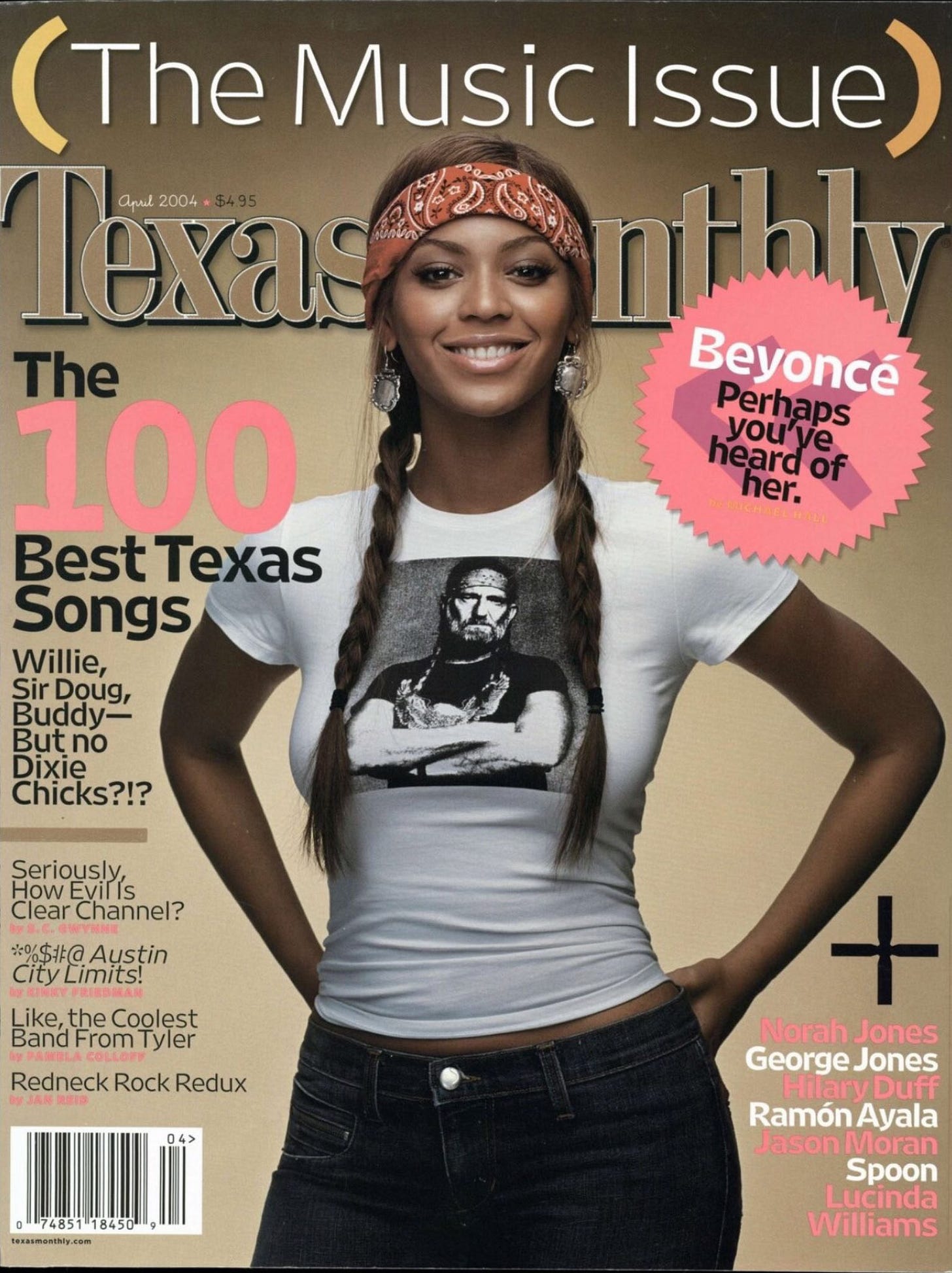

Beyoncé Makes America Great Again.

'Cowboy Carter' reminds us of when we could co-exist...on the radio, at least.

Country music has long been touted as American music. To many, the “country” in country music represents not only rural areas and the quickly fading agrarian lifestyle but also the United States itself. Fans boast that the stories told in country songs tell the story of America. The music is so strongly associated with America that in the last several years, the part deemed “too country” for country radio was cordoned off - along with other “roots”-based genres - under the label of Americana. So it should come as no surprise that the cover of Cowboy Carter, a celebration of the many diverse forms of American music, depicts an American flag-waving, chaps-wearing Beyoncé side-straddling a white stallion. Unlike the stationary mirror ball horse she sat atop on 2022’s Renaissance, Cowboy Carter features a white stallion in a confident, casual gallop, carrying Beyonce into town to reclaim the music of her heritage, which is ultimately the music of America.

Cowboy Carter is not only a celebration, it’s a proud, defiant one. It’s a celebration of the music that brought us all together, over and over throughout our country’s history, against the wishes of those who feared our convergence; it’s much easier - for their purposes - to divide and conquer. Beyoncé is reminding us, explicitly and metaphorically throughout this album, that she belongs at the party that, over the last century, has been almost completely taken over by white people, and mostly white men. Not just country music, but rock and blues as well.

Make no mistake, Cowboy Carter is not a country album. It’s a celebration of, yes, Black America, but also American music in general. It could be argued, therefore, that it is an Americana album in its most literal sense. It reclaims country and blues music back from its white gatekeepers, it mixes it with soul and R&B just like Ray Charles, Etta James, Solomon Burke, Arthur Alexander, Tina Turner, and so many other Black artists did decades before. Before radio decided to divide everything and everyone. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 may have told us segregation is wrong, but radio didn’t get the memo, as within just a few short years after that, Black and white artists were each divided into their own pre-determined formats. Again, nothing new, as “hillbilly” and “race” records were the dividing terms of the ‘30s and ‘40s, but the ‘60s and ‘70s were supposed to be more progressive, right?

Cowboy Carter plays like a radio station from the wild blue yonder that bucks that thinking and takes us back to when we could hear the Beach Boys and Sly and the Family Stone and Patsy Cline side-by-side. A diverse listening experience that a new generation, thankfully, are starting to embrace, much to the shagrin of those in my age group who grew up believing that, for some bizarre reason, Jimi Hendrix was the only Black artist “allowed” to be played on rock radio, or that Charley Pride was the only Black singer “worthy” of having hits on country radio, or that Stevie Ray Vaughan’s blues should be played on rock radio, but not Buddy Guy’s.

Throughout Cowboy Carter, Beyoncé calls bullshit on these gatekeepers, while shining a light on those who laid the groundwork for her and so many others. Linda Martell is given her due, as she appears here twice, both times emphasizing the silliness of dividing music into into genres, therefore building walls - with gates - to keep out other forms that “don’t belong”.

Dolly Parton and Willie Nelson drift in and out here and there, like grandparents placing calming hands on the shoulders of the bickering grandchildren. “Y’all, calm down,” they appear to say. “We approve of this mixing of ingredients. It’s what we’ve done since long before y’all came along.” Dolly with her blending of pop, rock, and country influences going back to “Here You Come Again” in the ‘70s and “Tie Our Love in a Double-Knot” in the ‘80s; Willie with his celebration of jazz, American standards, western swing, blues, and gospel for well over his 60 years of recording.

Beyoncé’s done this, too, on Cowboy Carter. There’s R&B, country, pop, hip-hop, rock, gospel - all mixed and mashed and crafted into something completely, uniquely Beyoncé. She pays Parton’s “Jolene” a visit, who’s still out there with her bullshit, messing around with other women’s men. This woman, however, is too proud to beg.

There’s so much depth to Cowboy Carter, so much sprawl, that it can be overwhelming upon first listen. The best albums should be. Repeated listens are required. Something new unfolds each time - a sample here, a lick there, an unexpected twist somewhere else - that unites the past with the present and, most importantly, burns borders to the ground.

One need look no further than one of the album’s best moments, the fist-pumping anthem, “YA-YA”. Nancy Sinatra, the Beach Boys, Sly Stone, Mickey and Sylvia, all give an assist to Queen Bey as she struts and signifies deservedly into the void left by Tina Turner. It’s pure soul righteousness.

Guests add texture all through Cowboy Carter without drawing attention away from the mission. Miley Cyrus duets on “II Most Wanted” (with guitar from the War on Drugs Adam Granduciel, fiddle from Sara Watkins, and guitar from Sean Watkins - both of Nickel Creek). Post Malone drops in to add vocals to “Levii’s Jeans”. And on the cover of the Beatles’ timely and timeless “Blackbird” (here stylized as “Blackbiird” - the double i’s throughout the album titles are a reference to “Act ii” of a supposed trilogy that began with Renaissance), Beyoncé is joined by Black country artists Tanner Adell, Tiera Kennedy, Reyna Roberts, and Brittney Spencer, It’s one of the album’s most powerful moments, and it’s only the second song.

To add to the Americana aspect, North Carolina’s own Rhiannon Giddens contributes banjo and viola to the album’s first single, “Texas Hold ‘Em”, while Robert Randolph lays down his signature pedal steel sound on its B-side, “16 Carriages” as well as “YA-YA”. Fellow Texan Gary Clark, Jr., who’s staked his own claim to land that’s rightfully his, shows up on no less than four tracks (“Protector”, Desert Eagle”, “II Hands II Heaven”, and “Daughter” - which acts as a sort of sequel, or result, of Lemonade’s “Daddy Lessons”).

Then there’s “Bodyguard”. Beyoncé lays down a pop groove that doesn’t let up and would have fit right into the playlists of the Top 40 and AC stations of the mid-1990s.

And that voice. Beyoncé, as successful as she is, rarely gets the credit she deserves as a singer. Throughout these 80 minutes, she purrs, wails, growls, shouts, moans, and testifies. It’s a feast for the ears.

I haven’t always been a Beyoncé fan. I didn’t give Destiny’s Child a fair shake, I admit. It wasn’t my thing at the time. But every solo album has built upon the last. I started to really pay attention with her self-titled 2013 release. And if any album ever deserved the Grammy for Album of the Year, it was Lemonade. Maybe this album is partly a reaction to that snub. Maybe it is a reaction to her treatment at the CMA Awards when she performed with the Chicks. If so, then it’s wonderful to see art as powerful, challenging, and rewarding as this come from such circumstances.

Yes, it’s quite long, and no, it’s not perfect. But the distance between her ambition and the results is closer than many who attempt such grandiose Statements. No, Cowboy Carter is not a country album. In her own words, it’s a Beyoncé album. And like all the best works of art, whether it’s music, film, paintings, etc, it does not fit into an easily categorizable box. It exists as a unique vision by its artist, by its creator. These are the kinds of works that transcend not only their respective disciplines but remain timeless as the years pass. Cowboy Carter is the latest work that belongs in that conversation. It’s the kind of album that will be discussed for quite some time. It will open doors. It will be praised. It will be maligned. It will be called overrated. It will be called under-appreciated. No matter what, it will be talked about.

Will Cowboy Carter bring America together again? No. But its mixing of disparate sounds and collapsing of walls prove it could be a step in the right direction if we let it.

Seriously the lyrics to songs on cowboy Carter are instrumental in bringing America together? Really? Not that they’re anything to do with separatism but you’re stretching here.