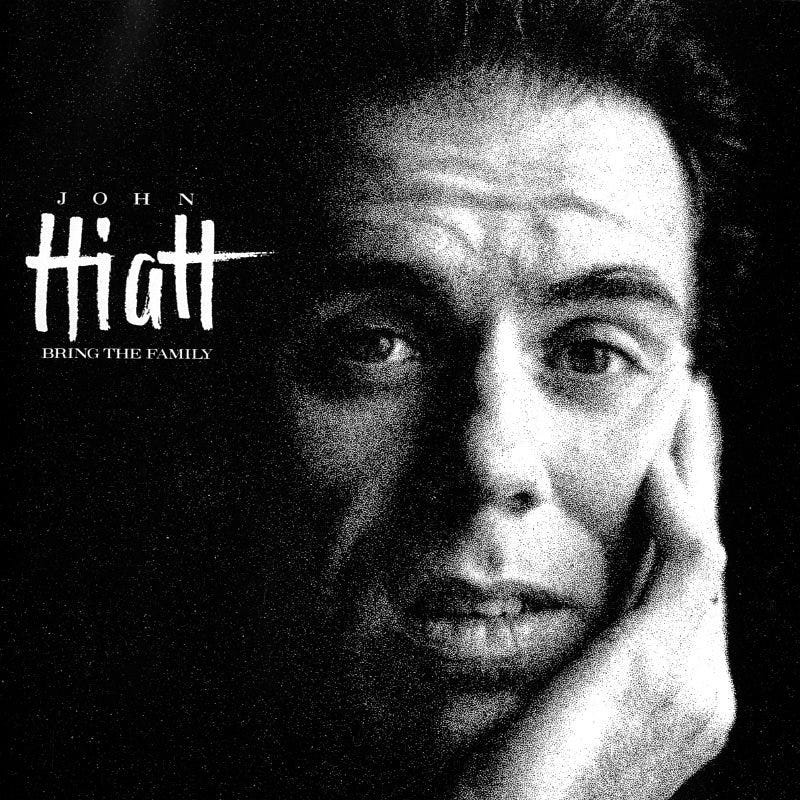

From the archive: 35 Years of 'Bring the Family'

Looking back at what became a landmark album for both John Hiatt’s career and an entire music genre that was yet to be named.

No new post this week, but to celebrate Bring the Family’s release this week in 1987, I’m re-upping this one for those who may have missed it initially.

Originally published May 29, 2022.

“I had just gone through a hell of my own making and came out the other side which had the effect of rendering all these other seeming monsters to be kind of toothless. They weren’t nearly as scary as any I’d created on my own.” - John Hiatt interviewed by Graham Reid, 1991.

By the mid-1980s, John Hiatt was considering giving up recording altogether and just living off royalties. After all, his songs were still being sought after and recorded. Maybe he could pick up some live gigs here and there. Maybe he could just join another band as he had done in the past with both Ry Cooder and Nick Lowe. Either way, Geffen had cut him loose, and to him, that was strike three. He was starting to think the record industry was trying to tell him something; they didn’t want him to make any more records.

One could hardly blame him for that outlook. By what was now well over a decade into a recording career, three major labels had dropped him. Geffen was the first label where he made more than two albums, yet they’d cut him loose, too. Although his songs were being noticed and, most importantly, recorded by more and more artists, and critics and fellow musicians were constantly lavishing praise, that big hit song, brought forth from his lips instead of just his pen, had so far eluded him. Still, he had two things going for him that he hadn’t had for quite some time: sobriety and a new love, and both were inspiring him to write about all these new experiences and emotions he was in the process of discovering.

“When you have a stable environment going for you, it gives you the courage to look at yourself and put what you see into your songs,” Hiatt explained in No Depression. “That takes balls, creating art informed by your life. A lot of people don’t want to know who they are. When they look in the mirror, they look past themselves. But what are the tough times good for if not to learn something, if only that you don’t know shit?”

That quote sums up John’s perspective during his newfound sobriety, which came before the suicide of Isabella, his second wife. At the time, he was living alone in an apartment over a garage, as he and Isabella had separated. In that little apartment, he would begin work on the songs that would become Bring the Family.

Bring the Family not only stood out from other rock and pop albums from the 1980s due to its more organic sound but also because of its subject matter. It was an album made by adults for adults. Released in the same year Motley Crue and Guns n’ Roses were celebrating the hedonistic lifestyle on the Sunset Strip with Girls, Girls, Girls and Appetite for Destruction respectively, Bring the Family represented adulthood, parenthood, sobriety, monogamy, domesticity, and responsibility - traditionally very un-rock and roll themes, and in fact, subject matter rock and roll rebelled against from its inception. In that respect, Bring the Family rebelled against the rebellion. Becoming a sort of 1980s version of Music from Big Pink, it shunned what was popular in favor of authentic sonics and mature values.

Memphis in the Meantime

On the opening, “Memphis in the Meantime”, Hiatt plays the role, no doubt autobiographically, of the frustrated singer-songwriter who isn’t exactly setting Music Row on fire with his songs. Maybe he imagined himself back at Tree, filling up reels and reels of tape with songs for every occasion and/or artist's style, only to be turned down time and time again. Maybe that frustrated singer-songwriter was more than ready to drive three hours west to Memphis for some charcoal ribs at Charlie Vergos’s Rendezvous, in the alley, downstairs behind 52 South Second Street. Maybe he imagined himself tuning into WDIA or WHBQ on the way in, listening to Rufus Thomas or Dewey Phillips spinning those hot R&B and blues tunes. Maybe after hitting town, he’d head to Beale Street and catch a live band. Not one with crying pedal steel, either, but one with those hot Memphis Horns and a Fender Telecaster played through a Fender Vibrolux Reverb amplifier, turned up to ten, of course.

Lyrically, the genius of “Memphis” also rests with the fact that the narrator isn’t sharing his experience or his intentions directly with the listener, instead, we’re listening in on a conversation he’s having with his partner/lover/spouse. She may be a performer herself (“You say you’re gonna get your act together, gonna take it out on the road”) but it’s obvious that, for now, they’re relying on his songwriting to get by (“Until hell freezes over, maybe you can wait that long / but I don’t think Ronnie Milsap’s gonna ever record this song). It’s not hard to picture a disheveled, frustrated wordsmith steeped in blues and R&B but eking out a living in Nashville trying to convince a fledgling country music-loving starlet to get good and greasy in a juke joint and a rib shack three hours away, where the soul of man never dies, as Sam Phillips would say.

Alone in the Dark

“Alone In the Dark” is a harrowing piece of music. The narrator describes a “still life study of a drunken ass” howling at the moon, alone in the dark, but not wanting to face the day; instead, he’s hoping the sun doesn’t rise too soon because he’ll then have to possibly confront his demons, or maybe just his friends and family: those concerned for his well-being. He doesn’t want to hear it. Right now, he’s having a dark night of the soul, an evening of “extreme self-pity.” It’s a process. Leave him alone.

It cuts even deeper, though. This is the singer’s last stand. If we are to take these songs as autobiographical - and for Bring the Family, let’s face it, we must - this is Hiatt’s moment of clarity. He cries, “I’m on my knees at last!” It’s an epiphany, the moment of redemption when all past sins are brought to bear. The boy who flunked religion in Catholic school is ready to confess. Only when he’s alone in the dark can he finally see the light.

The song features some of Ry Cooder’s most ferocious slide playing on record, cutting through the steady, ominous groove laid down by Keltner and Lowe. With Hiatt’s bluesy howl wailing over his understated acoustic strumming, the song succeeds in its effortless goal of being equally frightening and dripping with sexual tension. (Its sexiness didn’t go unnoticed by James Cameron, director of the 1994 action-comedy, True Lies, who, at the suggestion of star Jamie Lee Curtis, used the song to great effect as Curtis danced erotically for her movie husband Arnold Schwarzenegger, leaving him - and most moviegoers - speechless.)

Thank You Girl

Yes, there were moments of deep, deep lows on Bring the Family, but there was also plenty to celebrate, including finding his new love, Nancy, who’d help him out of the dark and into a lifelong journey of love and sobriety that continues to this day. With Cooder’s playful slide and Keltner’s driving beat, the music is as celebratory as the lyrics which boast, “If all men are equal, this must be against the law / ‘Cause I can’t help but feel that I’m one up on my brother when night falls.”

Lipstick Sunset

“We’d been out on this long, epic tour,” Sonny Landreth recalls. “We weren’t getting sleep. We’d just gone out night after night. Just before we walk out on stage, John goes, ‘Oh, by the way, I understand Mr. Cooder and Keltner have requested tickets for the night.’ And I said, ‘Really? You might have told me that sooner, you know! But maybe he did me a favor so I couldn’t think about it too much. “I was okay until we got to ‘Lipstick Sunset.’ So we’re getting into the song, and I think, OK, Ry’s out there; just don’t think about it. Do your thing. And then I realized I was playing a Fender Strat that used to be Ry’s guitar that he gave to John. So here I am, playing ‘Lipstick Sunset’ and Ry’s iconic solo, just one of the greatest things you’ve ever heard in your life, on stage. He’s in the audience. We haven’t had enough sleep; we’re just burned out. And that’s the only time it ever kind of got to me. I don’t know what kind of job I did. At any rate, it was kind of a moment; then after that, I was fine.”

“I got lucky that time,” Ry Cooder admits when speaking about that famous solo. “I didn’t overplay. Those days, if I got excited, I’d play too hard and too much, and I had to get cured of that. But on that one my nervous system was in good form, and I didn’t overdo it.”

Thing Called Love

“Bonnie found the song,” Don Was explains. “We both knew Bring the Family, but Bonnie’s the one that wanted to do (‘Thing Called Love’). And we had a hell of a time cutting it, too. It was the hardest song to record, and that was because of Jim Keltner. It’s this crazy juxtaposition. He’s got like two different feels going at once. It’s a shuffle against straight time, and without that, you can’t really do justice to the song. So we struggled with that for a long time, trying to figure out what was going on there, what was the thing that was making it dance.”

Keltner humbly credits Ry Cooder’s guitar work, however, as being the secret ingredient to that particular song’s success. “That’s Ry, that’s totally Ry,” Keltner confesses. “That’s Cooder at his best, his finest.”

Another change was to transpose the electric riff Cooder played over Keltner’s groove to acoustic guitar, which allowed Raitt more freedom to add her signature slide fills throughout the song, making it more radio-friendly than the original, which ultimately led to its success; success for both the artist and the writer. “The thing that really characterizes John's writing to me,” Was explains, “is that above all else, he’s an emotional writer that approaches it with talent, humor, and cleverness but never just for the sake of showing you how smart he is or showing you how clever he is. He does it without ego and always in service to the emotional content. I think ‘Thing Called Love’ is that kind of song. It goes very deep. I mean, ‘I ain’t no porcupine, take off your kid gloves,’ I’ve never heard anyone say that before. It’s so right.”

Stood Up

Here, John addresses his alcoholism in, well, quite sobering terms. It resonated with me at first due to its clever wordplay, but later, as I fought my own battle with alcohol, it became a validation of sorts.

After the first verse sets up the plot, with Hiatt recalling his first steps and his “schooling years,” we get to the second verse, where we hear the regret in his voice over the way he left the woman with the “flaming red hair” (most likely an allusion to his first wife, Barbara). “I didn’t know how to be a husband or what marriage was all about, or even what being an adult was,” John recalls of that time. “Not just because of my age, but by being so emotionally stunted by drugs and alcohol.”

It’s the third verse that brings it home, though. The regret of the previous verse is replaced by pride and resiliency revealed by his recent sobriety. He finds himself still playing music in those bars and clubs, but not partaking while relishing the fact that he’s not giving in to temptation ever again.

Tip Of My Tongue

“There was one song that we did that, later on, I couldn’t listen to,” drummer Jim Keltner recalls. “I just couldn’t get through it. That was ‘Tip of My Tongue.’ I never listen to it. I remember listening [to the album] in the car, and when that song came on, I remembered the story that Ry had told me about [John’s former] wife. And the story is about that. And I was just crying uncontrollably while I was driving.”

Your Dad Did

“He had an obesity problem and he gambled,” Hiatt recalls of his father. “Those were his two addictions: food and gambling. But this enormous man was so charming, funny, and wonderful. I mean, people at these home shows would just fall in love with him. He was a great storyteller, just a wonderful guy.” And he was great at closing the deal. “He was responsible for a lot of those harvest gold, avocado green, and burnt orange kitchens around the Midwest back in the early ’60s.”

“Your Dad Did” is Bring the Family’s best example of Hiatt’s sardonic wit: the suburban all-American dream with an underpinning of darkness just to keep you on your toes. “You love your wife and kids,” Hiatt sings with almost a sneer, “just like your dad did.”

Legacy

He’s not a household name like many of the artists that have covered his songs over the years (Bob Dylan, BB King, Eric Clapton, Rosanne Cash, Iggy Pop, Willie Nelson, Bob Seger, Emmylou Harris, The Everly Brothers, Paula Abdul, Buddy Guy, and so on), but John Hiatt is one of America’s greatest songwriters, and Bring the Family is his greatest album. In the years since its release, at least one of its songs has become a modern-day standard and covered by dozens of artists (“Have a Little Faith in Me”); one revitalized the career of blues-pop legend Bonnie Raitt (“Thing Called Love”) and was included on her Grammy-winning album, Nick of Time; and even a throwaway line on the album-closing “Learning How to Love You” inspired the title of an album that has sold over 21 million copies (Hootie & the Blowfish’s Cracked Rear View). In 1989, Rolling Stone awarded Bring the Family spot number 53 on their list of the top 100 albums of the ‘80s.

Have A Little Faith

Up in that above-garage apartment with only a little piano, for arguably the most famous song on Bring the Family, Hiatt reached back to those nights in his room listening to WLAC and those soul-stirring Gospel songs the DJ known as “The Hossman” would play. He started repeating a simple piano figure, over and over again until the words came:

When the road gets dark

“I'm not sure if I was singing it to myself...”

And you can no longer see

“Or if I was singing it to everybody in my life that I was trying to suit up and show up for but had no idea how to do that...”

Just let my love throw a spark

“And just the idea of having some faith in general, I think, which is what I needed at the time.”

And have a little faith in me

Listening to Bring the Family, one can clearly hear in the ballads John Hiatt searching for redemption as he works through his regrets, just as the up-tempo numbers celebrate his new life and marriage with the excitement of possibility.

It is in this sense that Bring the Family has its most profound impact on the listener. It can be enjoyed on the surface as an album that sways and swaggers with inventive, funky rhythms and inescapable hooks, yet it rewards close listening by revealing that adulthood can not only be just as exciting as adolescence but for one of the first times reflected on a rock album, it’s celebrated as being even more so.

For the complete story of Bring the Family and the circumstances surrounding it, pick up a copy of Have A Little Faith: The John Hiatt Story, available wherever books are sold in hardcover, as an e-book, as an audiobook, and in paperback.

Thanks for that. Am torn now - spin the CD or order the book? Here’s a Hiatt listening story. On a sunny LoCali Saturday afternoon in late January almost 30 years ago I went for a walk and brought along a portable player - not my normal MO. But why not ‘Bring the Fam’? My dad was sick and declining in a nursing home in my sister’s tiny town back in the Midwest. He was old and we’d all been together at Christmas, knowing what was coming. I was blocks away when Like Your Dad did came on. And then it quit in the middle of the song. When I got home my wife said call your sister.

I may have mentioned this before but it is timely to remind everyone who enjoyed ths piece Michael's book Have a Little Faith brings to the reader the entire 'enchilada' regarding Mr. Hiatt. It is a highly informative work I recommend wholeheartedly. Go for it.