From the archive: Don’t Bug Me When I’m Working: Little Village At 30

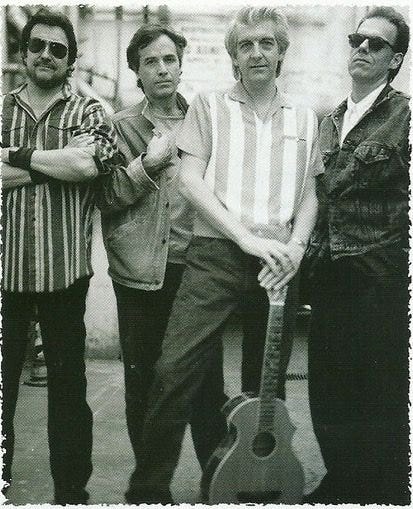

A look back at the only studio album by Ry Cooder, John Hiatt, Jim Keltner, and Nick Lowe released under the moniker Little Village, 30 years later.

Originally published February 18, 2022.

The following includes outtakes never before published from Chapter 13, “Don’t Bug Me When I’m Working,” of Have A Little Faith: The John Hiatt Story, available here and wherever books are sold.

“Go ahead, we’re rolling, take one.”

Leonard Chess was perched behind the board in the control room at 2120 South Michigan Avenue - the storied address of the legendary Chess Records - in Chicago, Illinois one afternoon in early September 1957. The label had recently moved into its new location (which was originally conceived and constructed by architect Horatio Wilson in 1911 and updated in 1956 by John S. Townsend Jr. and Jack S. Wiener) earlier that spring, where it would produce some of the most exciting and lasting music of the twentieth century and beyond. Towering figures in blues, soul, doo-wop, and rock and roll all recorded for Chess in that era: Chuck Berry, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter Jacobs, Etta James, and so on. On this day, however, Leonard was overseeing a session for Sonny Boy Williamson II, an artist from (it’s assumed) Glendora, Mississippi that had been with Chess’s subsidiary, Checker, for a couple of years, recording such seminal blues classics as “Don’t Start Me To Talkin’” and “Keep It to Yourself,” among many others.

Williamson was born Aleck Ford (somewhere between 1897 and 1912, no one really knows) but later changed his surname to Miller after his stepfather, Jim Miller. He picked up the nickname “Rice” as a child, due to his love of rice and milk. He would also occasionally go by “Little Boy Blue,” eventually settling on the nickname of the already popular bluesman John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson as his own. (The original Sonny Boy passed away in 1948.)

Not much is known of Williamson (we’re referring to Aleck “Rice” Miller, or Sonny Boy II as “Williamson” for the duration, so as not to fully confuse) in the first thirty years of his life, other than he used to pal around with Robert Johnson, Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, and Elmore James, playing music in various juke joints and parties, and on various street corners throughout the south. He also worked for tips with Robert Junior Lockwood, Johnson’s stepson, from Clarksdale, Mississippi to Helena, Arkansas in the late 1930s into the 1940s. After adopting the moniker Sonny Boy Williamson II, he appeared on KFFA in Helena with Lockwood during “King Biscuit Time.” The program was simulcast throughout the delta and he would tour as part the King Biscuit Entertainers during the better part of the forties. Williamson toured a few more years with the likes of Howlin’ Wolf and Elmore James before signing with Checker in 1955. He would live another ten years, influencing and later even sitting in with, an up-and-coming generation of white boys devoted to the blues, from the Yardbirds to The Band.

“Name It What You Wanna”

“What’s the name of this?”

Back at the board at 2120 South Michigan, Leonard Chess was, from his point of view, asking a simple question.

“‘Little Village,’” Sonny Boy Williamson II replied, his voice booming into the vocal mic with the confidence and devil-may-care attitude of someone who’s spent a lifetime singing, playing, and living the blues.

His reply is followed by just enough silence for one to be able to picture the look of confusion Williamson undoubtedly witnessed wash over Chess.

“A little village, motherfucker! A little village!” Williamson shouts. Not with anger or malice, but impatience.

Chess talks over him. “There's isn't a mother fuckin' thing there about a village, you son of a bitch! Nothin' in the song has got anything to do with a village!” In the background, you hear some of the musicians gathered at the session, a who’s who of Chicago blues session royalty (drummer Fred Below, bassist and bandleader Willie Dixon, pianists Lafayette Leake and Otis Spann, guitarists Eddie King Milton, Luther Tucker, and Williamson’s old sidekick, Robert Junior Lockwood) cracking up.

“Well, a small town!” Williamson attempts to clarify. Not that he really cares. He just wants to get on with the take.

Chess isn’t having it. “I know what a village is!” He snaps back. In the background, Lockwood, Milton, and Tucker noodle around as the two alpha males trade barbs.

“Well all right, goddamn it!” Williamson responds. “You know, you don't need no title! You name it after I get through with it, son-of-a-bitch! You name it what you wanna. You name it your mammy if ya wanna!”

With that, and a snare hit from Below as a final punctuation to Williamson’s mild annoyance at Chess, who’s laughing it off as he repeats, “Take one, rollin’,” the song “Little Village” begins.

That exchange - seemingly heated to virgin ears but just another day on the job for those who were there - though recorded in September of 1957, didn’t see the light of day until 1969 (after both Williamson and Leonard Chess had left this world) when it was released in a twelve-minute version, complete with false starts and all the fly-on-the-wall between-takes-banter, on the fantastic odds and ends compilation, Bummer Road. Leonard Chess had a habit of holding on to an artist’s work, not releasing it until he felt it was the right time. This could mean songs could sit in the vaults for months - years even - before they would hit the streets if they ever did at all. After Leonard’s death, the vaults were sifted through, and compilations like Bummer Road of several Chess artists’ material were packaged and released out into the world, supervised by Leonard’s son, and future head of Rolling Stones Records, Marshall Chess.

It Takes A Village

At least one copy of Bummer Road, or in particular the track, “Little Village,” made it to the ears of John Hiatt, Ry Cooder, Nick Lowe, Jim Keltner, and/or then-president of Warner Brothers Lenny Waronker, because “Little Village” was chosen as the official band name of the four musicians that had been reassembled to grace the world with another album - and this time a world tour - for the first time since recording the now-classic John Hiatt album, Bring the Family over four days back in February of 1987.

“I think Ry came up with that,” John Hiatt replies when asked who suggested the name, Little Village. As for what brought Hiatt, Ry Cooder, Nick Lowe, and Jim Keltner back together for the first time since Bring the Family, “We just thought it’d be good to make another record together and have it not be one or the others’ solo records. We thought it'd be fun to make a record as a band.”

Ry Cooder recalls, “It seems to me that Keltner and I were sitting around one day. ‘What could we do?’ We talked about John and we talked about Nick. ‘Well, what if we were a group but not as a hired backup band for Hiatt, but as a cooperative band, you know, as a real band. So then the calls went out and we went to Lenny Waronker.”

Nick Lowe explains, “I think because Bring the Family was so well received, and people were so excited about it, I think that got Lenny Waronker to get his checkbook out. And in a way, that was one of the reasons why the record didn't really work.”

Lenny Waronker, a second-generation record man (his father Sy started Liberty Records) who grew up in Hollywood and was childhood pals with Randy Newman, started working under Mo Ostin at Reprise as an A&R man. Over the years, he helped build Warner/Reprise into one of the most powerful and respected record companies in the world, guiding the careers of everyone from Neil Young and Joni Mitchell to Little Feat, Rickie Lee Jones, and the Doobie Brothers. He also threw his label’s support behind the Traveling Wilburys, a “supergroup” - Bob Dylan, George Harrison, Jeff Lynne, Roy Orbison, and Tom Petty - that came together quite organically at first.

In January of 1987, a month before Jim Keltner would meet up with Cooder, Lowe, and Hiatt for the four-day session that would become Bring the Family, he had started working with George Harrison on the ex-Beatle’s next album, the Jeff Lynne-produced, Cloud Nine.

Keltner remembers: “The Wilburys came about from Jeff and George when we were doing Cloud Nine at Friar Park (Harrison’s estate in Henley-on-Thames, England). That record was Jeff's first time working with George, and they really got on well, having fun. One particular night, I remember they were being really silly with that crazy Monty Python type of humor that we all love so much. And they were saying all these silly names: Willoughbys - something about Willoughbys, I remember; the “Climbing Willoughbys” and then the “Traveling Willoughbys” and then...it somehow finally worked its way to the Wilburys.”

The debut album by the Traveling Wilburys, Volume One, was released in October of 1988, eventually selling over three million copies in the US. In light of its success, Waronker figured the public - especially middle-aged, money-making, spend-happy baby boomers would be hungry for more Avengers or X-Men-style groupings of veteran musicians, or “supergroups.” After all, this was a generation that grew up with the likes of Cream and Blind Faith. They were no strangers to superstars collaborating.

Aside from the commercial aspect of it, Waronker was a big fan of Rockpile, the rock and roll powerhouse composed of Dave Edmunds, Billy Bremner, Terry Williams, and Nick Lowe who were responsible for, among others, Lowe’s Labour of Lust album and Dave Edmunds’ Repeat When Necessary, both from 1979 and, sadly, their only album under their own name, 1980’s impossible-to-live-up-to-its-hype-but-still-not-bad-at-all, Seconds of Pleasure. Rockpile had Nick Lowe, Lowe had produced side two of Hiatt’s Riding With the King album, Hiatt had toured with both Lowe and Cooder over the years, and with Keltner, all four had played on the now-classic Hiatt album, Bring the Family. Waronker had been associated with Cooder going back to his first album, and Cooder had also played on Randy Newman’s landmark, 12 Songs. It all started adding up.

Since the Bring the Family lineup had never toured, fans of that album were undoubtedly hungry for a reunion. Why not give it a shot? The fact that the Wilburys were still fresh on everyone’s mind and that Keltner was also that outfit’s drummer (under the alias, Buster Sidebury), couldn’t have hurt, either.

“We all have a lot of respect for each other, that helps,” Hiatt admitted in 1992. “I’ve worked with Ry since 1980 and he's taught me a lot. He was the first guy I felt that really liked the way I played guitar. It meant a lot to me. Nick is a natural bass player with a sound you can hang your hat on. Jim is the most musical drummer I've ever worked with. He's the secret ingredient for the band... the outside curveball that made it all interesting.”

Ry Cooder admitted in the press materials for Little Village’s self-titled album, “For years I thought I was missing something because, for my money, bands make the best music. It might be the Louis Amstrong/Earl Hines band or Sleepy John Estes and Hammy Nixon or whatever, but you get a buzz that way...a spin. Things happen that you can't predict and sometimes you get more than just what you put into it. Anyway, I've been slogging along for a while, having an okay time, but I realized that I really wanted to be in just that kind of unpredictable situation. I wanted to be pulled along by something in an unknown direction. Keltner, who I've worked with for going on twenty years, and I talked a lot about this and when we got together to do John's Bring the Family with Nick on bass, we came up with a really good quartet sound. Eventually, amorphously, it just kind of pulled itself together. It's miraculous, I think.”

At the same time, Cooder was still apprehensive about the band dynamic. “I always thought bands were a hotbed of fighting and contention and that you had to throw tv sets out the window, or something.”

The Songs

It all comes down to the songwriting, and Little Village had three exquisite master craftsmen - and one secret weapon - all working together. The results may not have been revelatory or groundbreaking, but taking a closer look at the songs that comprise Little Village 30 years on, it’s obvious that most of them were not really given a fair shake due to unrealistic expectations.

“Don’t Go Away Mad” for instance, sneaks into your subconscious. With lyrics that turn the old line, “don’t go away mad, just go away” on its head: “don’t go away mad, stay here and be angry, too,” the track is just plain infectious. The melody has the hook, yes, but what shouldn’t be overlooked is the rhythmic template. Keltner is a master of groove and rhythm; as anyone who’s played with, or even watched him over the years will attest. In fact, many of the more interesting moments musically on Little Village occur due to the help of Keltner’s wacky but inventive grooves and that guitar compost of his.

“Inside Job” is another highlight of Little Village. Keltner’s “crazy sequence sounds” lay down the groove until Hiatt’s voice slides over a subtle guitar figure. The song finds John Hiatt in pure soul mode, with a feel that wouldn’t sound out of place on any Robert Cray album. Hiatt’s falsetto hits in just the right spots. After the first chorus, the intensity picks up; Keltner comes in on the full kit and the track starts grooving even harder as the soul flows deeper. Hiatt sings of giving love to get love, and by keeping it inside, a relationship will never realize its full potential. As he sings, “it was an inside job, but baby we worked it out.”

Invariably, comparisons were made between Little Village and this lineup’s previous effort, Bring the Family. Although there were some fun moments on Family (“Memphis In the Meantime” being the most obvious example), “quirky” would not be the first thing to come to mind when one thinks about that album. Whereas Little Village seemed steeped in quirk. Its opening track is “Solar Sex Panel,” to drive the point home. Based around the old bald man’s joke that his baldness is actually a “solar panel for a sex machine,” the song includes such phrases as “I’m an ultra-violet penetrator.” Not exactly high art (but neither was “Since His Penis Came Between Us'' for that matter). Actually, it could’ve been seen as a perfectly apropo anthem for a middle-age man in the early 1990s. The chorus was catchy, that inimitable Keltner groove was irresistible, and the lyrics were cheeky without being vulgar. Not a bad way to open the album, even if it was no “Memphis In the Meantime.”

"’Solar Sex Panel’ is a cheerful song for people who find themselves losing their hair,” Lowe explained in 1992. “The idea is that it's really a divine intervention that you're developing this patch on your head to take rays in that will improve your life in every way.”

Keltner added, “it's about not worrying when you get bald. It just means you've got more testosterone than other guys, that's all.”

Cooder clarified, “Actually, it's an ecological love song that simply says love energy is clean and non-polluting. We're burning clean.”

Cooder, Hiatt, and Lowe all traded lead vocals for the album’s first single, “She Runs Hot.” “All you need to write a song is a little something to kick you over the edge,” Hiatt explained in 1992. “Ry is always collecting titles, like the song ‘She Runs Hot.’ My natural inclination was to put it in a car motif and place it in Hardin County, Tennessee, where I’ve been spending some time lately. a popular bootlegging territory.”

Hiatt also elaborated to Graham Reid in 1991 on research he did by looking through Low Rider magazine that led to coming up with the idea for “She Runs Hot.” “There’s a wonderful subculture of car worship here in Southern California among Mexican-Americans where they chop cars to the ground, install elaborate hydraulics and then have these hopping contests or go cruising down the boulevards. Because I came from Indianapolis where they have the Indy 500 I’ve always been into cars. In this magazine, they have these open love letters in a column at the back and it’s very touching...so open and direct and ultimately more poetic than anything I could come up with. It’s very inspiring and that stuff just gets to me.”

Do You Want My Job?

Looking back, it’s understandable to hear how as a group they reached the sound they had on Little Village. They all had an offbeat approach and they weren’t afraid to show their senses of humor on their (Hiatt’s, Cooder’s, Lowe’s) own albums. At the same time, that sense of humor could turn dark, or the following song could completely change direction emotionally and become captivatingly sincere or devastatingly heartbreaking. The need for strong, committed companionship in “Big Love” and the immense sorrow laid bare on “Don’t Think About Her When You’re Trying To Drive” being the most obvious examples here.

“You wait to see what's going to work,” Ry explained in 1992. “You look for tile signs. ideas start to accumulate and gather their own momentum and pretty soon it's like greased lightning. The ballads are the ones to watch because they have to be real. Anybody can rock and twang and get off on the energy and hope for the best, but a ballad has to touch the emotions.”

As far as ballads go, “Big Love” is probably the closest Little Village comes to the sound listeners may have been expecting due to the impossibly large shadow cast by Bring the Family. Acoustic guitar-based and a simple chord progression add up to the album’s most traditional arrangement. The tempo is at tortoise speed; it’s as if Keltner’s beat is suspended in mid-air each time before the two and four. Lowe’s bass anchors the song while Cooder’s slide is at its most biting and guttural. It cuts out of the dark like a moaning beast, punctuating the soulful pleas of Hiatt’s vocal. It’s spare, it’s powerful, it’s the album’s best moment.

On the flip side, “Don’t Think About Her When You’re Trying To Drive,” a fan favorite, is a surprisingly slick production, complete with keyboard strings and radio-ready reverb. It wouldn’t have sounded out of place on a Jimmy Buffett album at the time, yet it proves once again how adept Hiatt was at crafting radio-ready pop diddies when the need arose. An almost quiet storm-type R&B melody rides atop beautiful guitar work by Ry and sympathetic straight-ahead rhythm section work from Lowe and Keltner.

"Don't Think About Her When You're Trying To Drive" was a Ry title,” Hiatt revealed in 1992. “When we started working on the words together, we'd fax the version back and forth, me in Nashville and Ry in LA. That's the way things evolved.”

Little Village closes with “Don’t Bug Me When I’m Working.” All three vocalists once again trade verses, this time elaborating on the warning of the title (“I’ve got a job to do...I don’t work for you,” etc). The music, naturally, is off-kilter yet infectious, and it all comes full circle as it concludes with - what else? - the audio of Sonny Boy Williamson II yelling at Leonard Chess, “Little village, motherfucker! Little village!”

Don’t bug me when I’m working, indeed.

For the complete story of Little Village, including new, original interviews with all four members, be sure to pick up a copy of Have A Little Faith: The John Hiatt Story, available here and anywhere books are sold. Also available as an e-book and audiobook.

To dig even deeper, check out this The Record Player podcast where I discuss the album with hosts Matt Wardlaw and Jeff Giles.

My first ever CD and an all time favorite. Thank you for this, Michael.

I have this album and love it.