Truth'll Set You Free: Talking With Mother's Finest About 'Another Mother Further'

Co-founders Joyce 'Baby Jean' Kennedy and Glenn 'Doc' Murdock, along with producer Tom Werman, discuss the defining album of a multi-racial hard rock institution.

“You funny,” Joyce ‘Baby Jean’ Kennedy grins while I’m asking my first long-winded - and, I admit, mostly rhetorical - question: Why wasn’t Mother’s Finest a bigger success, and why was it so hard for a (mostly) Black rock band to get played on album rock radio in the ‘70s?

“You say you don’t know why? Come on, dude,” she laughs. “You know why.”

The history of rock’n’roll is littered with tales of should’ve/could’ve-beens and almost was’s. Mother’s Finest is one of the most frustrating examples of a group that had every element in place, every reason to hit it big, but just couldn’t make it happen for any number of reasons, most of them out of their control. It wasn’t just rock radio shutting them out, either; R&B and, later, Urban stations all but ignored them as well.

“Why Isn’t Anybody Here?”

It’s been 50 years, so accounts differ about exactly when and where Mother’s Finest was “discovered” by the team at Epic Records.

“We were playing at some place,” Glenn ‘Doc’ Murdock explains. “There was a young guy that saw the band and he worked for CBS as a runner. He told us, ‘You guys are really good. Are you recording with anybody?’ Well, we weren’t. We were just playing where people would have us. He said, ‘I’ll be back.’ A couple of days later we played another gig.”

“That was where we met Tom Werman,” Joyce adds.

Werman, who at the time worked A&R at Epic Records, recalls dropping by Alex Cooley’s Electric Ballroom in Atlanta one night with his colleague, Gregg Geller.

Depending on who’s telling the story, it was either in 1974 or ‘75, during the label’s winter convention, or while Werman was working on Ted Nugent’s self-titled album and received a tip from Derek St. Holmes about Mother’s Finest.

“The Atlanta meeting was our annual Winter sales conference, attended by the U.S. organization, and was held in 1975,” Geller recalled in an email. “It was 1975 because we reported our enthusiasm back to our brand new boss, the recently named head of Epic A&R, Steve Popovich. Had it been 1974, Don Ellis would have been the head of A&R, but I remember telling Popovich about the band.”

“Their performance was jaw-dropping,” Werman recalls now. “I had no idea who they were, or maybe somebody had asked me to go see them. I can't remember.” He pauses. “I think it was their manager, Hugh Rogers. What a character! I think he had gotten in touch with me and asked me to go [see them].”

“I have a vague recollection that [Tom] was invited by the band’s then-manager,’ Geller confirms. “This was before Tom’s involvement with Ted Nugent so it’s doubtful Derek St. Holmes had anything to do with it.” As for a runner hearing the band first and then returning with Werman, Geller replies, “Could an Atlanta-based Epic staffer have planted the seed? Sure, though I don’t recall anyone ever taking the credit—which staffers are wont to do.”

Either way, Mother’s Finest made enough of an impression that Werman made it his mission to get them signed.

“You know, I hate the term, but I was blown away,” Werman admits. “I'd never quite seen a band that good on stage. They were white and Black and rock and funk, and Joyce was ridiculous. I mean, she was just a fireball. I looked around after the show and I said, ‘Why isn't anybody here?’ I didn't have one little moment of doubt or uncertainty. And I was lucky enough to wind my way into the producer’s chair.”

Mother’s First

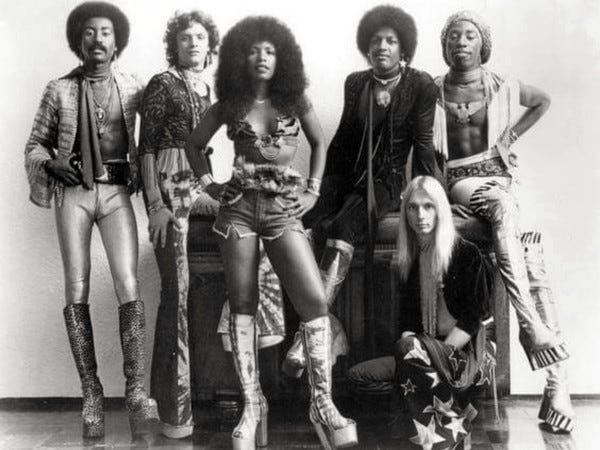

The origin of Mother’s Finest dates back to 1965, when an 18-year-old Joyce Washington - originally from Anguilla, Mississippi, but living in Chicago since she was seven where she adopted the surname of her stepfather, Kennedy - first met Glenn Murdock in a Chicago club. Joyce had a single out a few years earlier that became a regional hit. Glenn was singing in a Motown-like vocal group. According to Joyce, there was an immediate attraction. 59 years later, they’re still together.

After first seeing guitarist Gary Moore (known to everyone as Moses Mo - or just Mo - to avoid confusion with the late British guitarist) playing in a blues club in Dayton, Ohio, they invited him to join them. Along with drummer Doug Thompson, they headed down to Miami where they met bassist Jerry “Wyz” Seay, or “Wyzard,” a bassist who, since the age of 13, had shared stages with the likes of the legendary Jackie Wilson.

After recruiting Raleigh, NC’s Michael Keck for keys and drummer Donny Vosburgh from a Vegas showband (Thompson volunteered for Vietnam), the newly-christened Mother’s Finest (they originally named themselves the Motherfuckers, but thought better of it, yet kept the initials) signed to RCA and released a less-than-stellar debut in 1972.

Buried in overdubs of strings the band didn’t anticipate, the album didn’t play to their strengths or reflect the energy and fire of their live shows.

Enter Tom Werman.

“I Don’t Know, but I’ve Been Told…”

Hired by Clive Davis back when Epic was still small - mainly home to the Yardbirds, the Dave Clark Five, and Jeff Beck - Werman recalls, “I wanted a job at Columbia, but there weren't any. So Clive put me at Epic, and I went through two or three bosses.” During his first five years in the A&R department, despite seeing some movement with his first signing, REO Speedwagon, the label rejected the next three acts. “I tried to sign KISS, I tried to sign Rush, and I tried to sign Lynyrd Skynyrd. I had them all free and clear, and my boss turned them all down.” Then he finally struck gold (platinum, actually) with the signing of Ted Nugent. That’s when Werman also ended up in the co-producer’s chair for the first time.

Nugent’s self-titled solo debut went platinum in 1975. “After that, I was a producer,” Werman laughs. “In the record business, there’s not a whole lot of depth. It’s either, ‘What have you done? Who are you?’, or it’s ‘Oh, you’re beautiful, babe! You’re an overnight success!’” (Although he ended up being the producer for several Nugent albums for the rest of the ‘70s, Werman is quick to point out, ‘Ted and I never talked politics.”)

“He’s the only one who touched this band and touched it right,” Joyce affirms when Werman is brought up. “I’m serious. Everybody tried but he had a knack. He knew how to let us go and let us do our thing. He didn’t govern us. He was there as an extra ear and an extra head, which was the beauty of it.”

Not long after that fateful night at Alex Cooley’s Electric Ballroom, Mother’s Finest was signed to Epic. By this time, Donny Vosburgh had been replaced with a new drummer, Sanford “Pepe” Daniels, who played on what became their self-titled debut for Epic.

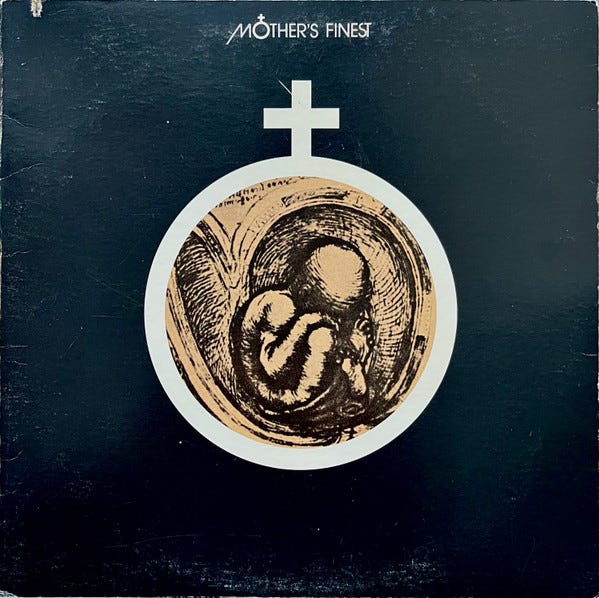

Recorded in Florida at Miami’s famed Criteria Studios and released in 1976, Mother’s Finest could finally show what the group was capable of on record. It was loud. It was forceful. It was tough. It rocked. It funked. It grooved. “I think we had a little action [with the record],” Werman recalls. “I think maybe ‘Fire’ was a single.”

“Fire” kicked off the album with metallic riffing by Mo before it transformed into a full-on gospel/rock assault. It was immediately followed by the epic, adventurous, "Give You All the Love (Inside Of Me)." “For anybody to hear ‘Give You All the Love’ and not say, Holy shit! Who are these people?” Werman enthuses. “I mean, it's a musical journey, that song. It's just beautiful and that guitar solo? God, they’re good.”

But it was the third track that raised eyebrows throughout the industry.

As Joyce told Classic Rock in 2022:

What [Doc] was saying with that song was the truth. He’s courageous like that. The whole idea was: Blacks don’t do rock’n’roll anymore, even though they started it, so we’re gonna do it – right here, in your face!

Although several Black groups had rock elements in their music in the ‘70s (Funkadelic, Rufus, the Isley Brothers), most were cordoned off into non-rock radio formats and in non-rock (funk, R&B) bins in record stores. In the case of Mother’s Finest, rarely were they discussed without the term “funk” hyphenated onto “rock,” as if it needed to be qualified.

By the time their Epic debut was released, the band had replaced Pepe with another drummer by way of Chattanooga, Tennesse, Barry “BB Queen” Borden. (Even though Borden is pictured on the cover of Mother’s Finest, Pepe played drums on the record and given credit in the liner notes.) Their classic lineup was now solidified.

“We wanted to be a band that people could find a personality within it that they were attracted to,” Joyce explains. “You had two frontpeople, an eclectic bass player, a vibrant little white boy on guitar, and you had this glorified little white boy on drums, and you had a keyboard player from Raleigh, North Carolina. It was something that happened when those spirits got together, that music just created itself.”

Too Black for White Radio, Too White for Black Radio

Even though their Epic debut was overflowing with funk-rock firepower, it didn’t make the impact on radio or in the marketplace that either the band or the label was hoping for. That didn’t stop them from trying again.

“It was a development thing,” Werman explains. “I mean, we weren't bummed out. We were just saying, Let's build on what we've got so far.”

The band did just that when they headed back to Criteria with Werman to record the follow-up.

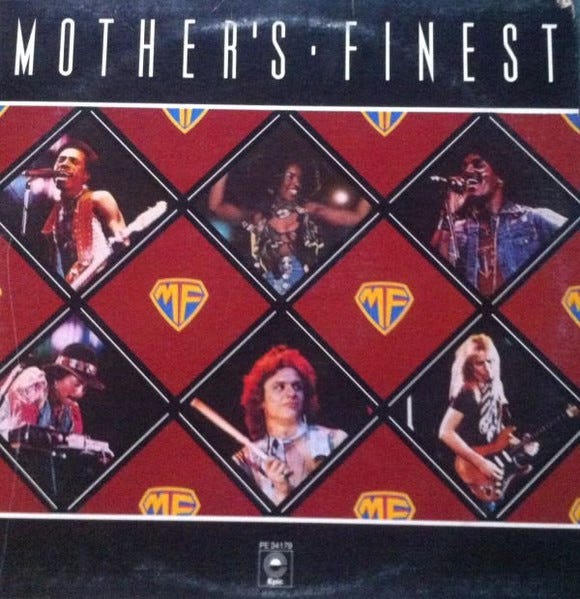

“That was recorded on 16 tracks,” Doc recalls of the band’s magnum opus, Another Mother Further. “God and the quality we got was so amazing. That’s why it’s one of our best because the quality still stands up today.”

“And we still sound the same only heavier,” Joyce adds. “And maybe better in a lot of ways, too.”

Another Mother Further is the most successful blend of rock and funk the band has yet to put on record, many of which are still staples of their live shows: the jagged stop-and-start funk of “Truth’ll Set You Free” and “Baby Love;” an incendiary take on “Burning Love” (the album was released the same year Elvis died); and Doc’s testifying on the driving, statement-of-purpose boogie, “Hard Rock Lover” were just a few of the highlights.

Then there was the opening track, “Mickey’s Monkey.” The idea of repurposing Smokey Robinson and the Miracles’ “Mickey’s Monkey” onto the riff from Led Zeppelin’s “Custard Pie” came about at soundcheck on an afternoon before a gig. “We weren’t purposely trying to steal from them,” Doc says now. “The band was downstairs and I was in the dressing room. They were playing ‘Custard Pie’ and, to my ears and through all that wood, it sounded like ‘Mickey’s Monkey’. So I started singing it to myself and I didn’t have to change anything. So I ran downstairs, jumped on the mic, and sang ‘Mickey’s Monkey’ right in the middle of it.”

It wasn’t a new concept. As long as bands have been jamming in garages or rehearsing and sound-checking before a show - hell, since Francis Scott Key - we’ve been mashing the lyrics of one song into the music of another. (Within the last decade, Chris Stapleton famously co-opted the music of “I’d Rather Go Blind” for the lyrics of “Tennessee Whiskey.”) Yet what Mother’s Finest did with “Mickey’s Monkey,” even if unwittingly, was take back the blues - and rock’n’roll - from a band notorious for appropriating songs by Willie Dixon, Sonny Boy Williamson, and, in the case of “Custard Pie,” Blind Boy Fuller and “Sleepy” John Estes, while claiming them as their own. But hey, that’s rock’n’roll.

On the track, “Piece of the Rock,” Mother’s Finest pledged their allegiance to rock’n’roll with the verse:

A rock star lookin’ for another million-seller

DJ said, ‘You can’t have none’

Well, go on and play your disco music

I’m gonna rock and have a whole lotta fun

That track, along with “Dis Go Dis Way, Dis Go Dat Way,” a send-up of the disco sound, left no doubt about where Mother’s Finest came down on the rock vs. disco divide that had just begun stirring at the time (but was still a couple of years away from boiling over).

Joyce and Doc give Atlanta’s legendary rock station, WKLS - 96 Rock, credit for giving the band a platform by airing “Piece of the Rock.” “They made it all happen,” Joyce says. “They were powerful, they were strong, and we did every interview they ever asked us to do. They were the reason why we reigned over the South. If every [radio station] had been as true blue and visionary as 96 Rock was, maybe we’d be talking another story now for Mother’s Finest.”

As for acceptance by radio most everywhere else, and the music industry in general, “It was always difficult,” she admits. She remembers when they were once invited to their label’s headquarters. “They had two floors. They had a Black music floor and then they had a rock floor. And again, we were somewhere in between! We went to the Black floor and had one conversation and then we went to the rock floor and had another conversation —”

“[The fact that] those floors existed,” Doc interjects “[represented] the separation of music. And this executive told us that we were never gonna have our picture on the back of a white kid’s door —”

“Or on an album,” Joyce adds.

Werman recalls, “Our head of promotion at that time - he was a Black guy, but he promoted everything - he said that Black radio thought it was too white, And white radio thought it was too Black. His quote was, ‘It fell between the chairs.’ I was not a powerful guy then; I had no real clout. But that was the biggest load of crap that I ever heard in 12 years of doing that.”

[****After this article was published, Gregg Geller emailed to counter Werman’s account above: “It was the head of marketing, not the head of promotion, who was responsible for the ‘it fell between the chairs’ quote,” Geller writes. “I don’t think there was such a person as a Black head of promotion in the record business in the mid-1970s though, to be fair, a Black head of marketing was probably a first for Epic Records among major labels in that era.” ****]

Doc continues, “Gamble and Huff came in one time while we were recording ‘Piece of the Rock,’ and they just stood in the corner with their hats and long black coats on and their arms folded.”

“They didn’t get it,” Joyce laughs.

“And they asked us,” Doc recalls. ‘Why are you doing this type of music?’ We told them, ‘This is what we feel. We thought it was appropriate to do what we felt and not pigeonhole ourselves into one category or another.’

“The bass player from Earth, Wind & Fire asked us the same thing about Mickey’s Monkey,” Joyce added.

“‘Why didn’t y’all put no funk on the record?’, Doc laughs.

“We just had to look at him and go, ‘Dude!,’” Joyce says. “He didn’t get it either.”

Looking back over their career, Joyce puts it all in perspective, “We dealt with that madness all these years. We've survived it, and God only knows why but we've never had any trouble. We've played some of the smallest clubs you could find in the deepest south, and we've gathered a following that is as loyal as the first day we ever played for them.”

“It was a business move.”

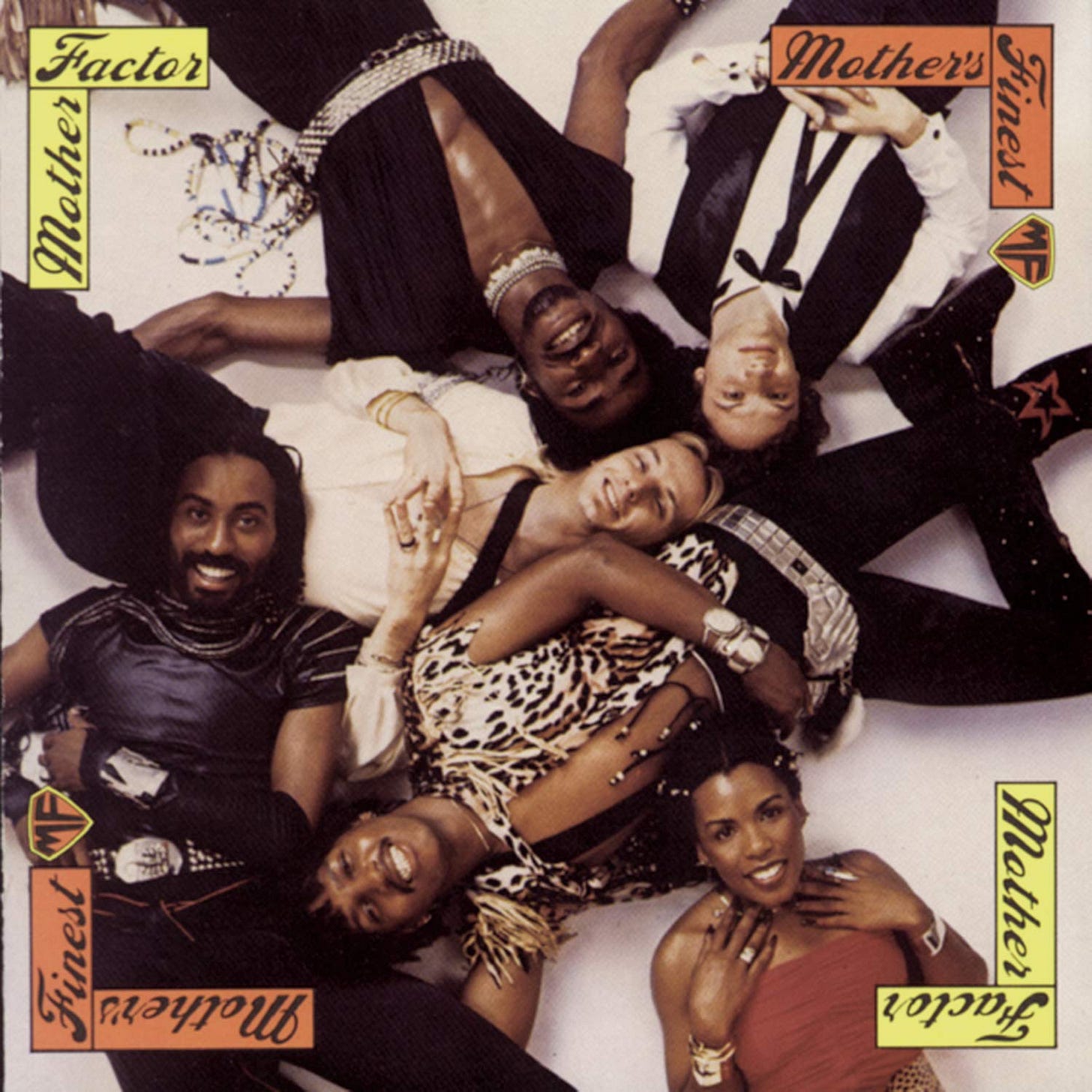

Even though they saw more critical acclaim with Another Mother Further - and even some chart action - there was some nervousness in the MF camp and at the label. Concessions were made. The album cover to their next release, Mother Factor, gave away its contents right down to its font choice for the title; the rock was toned down to curry favor with Black Radio. (It was also telling that Skip Scarborough - who’d written several hits for R&B artists over the years (Earth, Wind & Fire, Con Funk Shun, The Emotions) - was brought in to produce the album.)

Although it opened with “Can’t Fight the Feeling,” which remains in their live set to this day, the most memorable moment on Mother Factor came from the single “Love Changes.” (It was covered by Jamie Foxx and Mary J. Blige in 2005.) A live album followed in ‘79 that captured the group in its element, but it would be their last for Epic in the ‘70s. They turned up the guitars again for 1981’s metallic Iron Age on Atlantic. That same year, Joyce guested on Molly Hatchet’s Werman-produced Take No Prisoners album for “Respect Me in the Morning.”

After 1983’s One Mother to Another (which interestingly only showed Joyce on the front cover, and the rest of the band in small blocks on the back), Mother’s Finest called it quits for a few years while Joyce pursued a solo career. They reformed for 1989’s Looks Could Kill (on Capitol) with Glenn and Joyce’s son, Dion Derek Murdock, now behind the kit. (BB Borden left in ‘83 and joined up with Molly Hatchet for their No Guts, No Glory album - again, produced by Werman. BB later joined the Outlaws for a stretch and has been with the Marshall Tucker Band since 1997.)

Looks Could Kill could have - and should have - been the breakthrough they’d been waiting for. The timing was perfect. Hard rock and heavy metal were fully mainstream in 1989. Just the year before, Living Colour had released their debut album, Vivid, on - yes - Epic Records. An unapologetic hard rock band that was loud, brash, fierce, and Black, Living Colour enjoyed heavy rotation on MTV and rock radio. They even won a Grammy for Best Hard Rock Performance for “Cult of Personality.” Meanwhile, out of Washington, D.C., Bad Brains had spent much of the ‘80s mixing hardcore punk, reggae, funk, and metal into one exciting stew. 1989 was also the year Lenny Kravitz - marketed as a rock artist right out of the gate - issued his debut, Let Love Rule. The stage was set for Mother’s Finest to remind everyone where it all came from.

But it was not to be. Instead of a brain-shaking slab of heavy funk rock from a band that had helped perfect the sound, Looks Could Kill included all the trappings of bad late-‘80s pop and generic R&B. More Jody Watley and Janet Jackson than “Baby Love” or “Fire.” (Interestingly, also in 1989, The Veldt, a group from Raleigh, NC fronted by twins Daniel and Danny Chavis, signed with Capitol Records. Although the group would go on to brief critical acclaim in the ‘90s and are now seen as pioneers in the alternative/shoegaze arena, Capitol ultimately shelved their album, mainly because they “didn’t sound Black.”)

Joyce puts Looks Could Kill in perspective. “We had split up for six years,” she explains. “We were trying to come back together and we thought maybe we should take a different approach. It was a business move. [We were] trying to make it more pliable for the record company.”

“That was probably the worst move we ever made,” Doc adds. “We don’t have any excuse for that.”

As for Living Colour’s ascension, Joyce recalls, “We were split up when they came up. I remember that. I said, ‘Welp, there it is.’ We watched it happen. I mean, there ya go. Somebody opens the door, and somebody else goes through it. What are ya gonna do?”

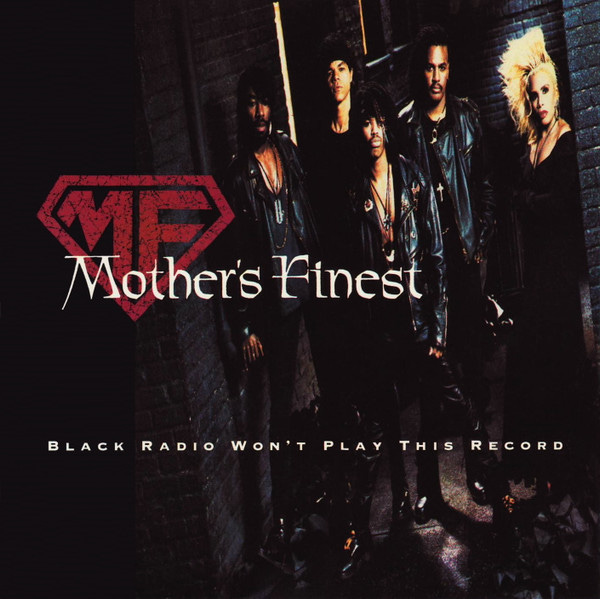

A Little Too Belligerent

What they did was keep playing. In 1992, just like they did with 1981’s Iron Age, they stopped trying to cater to the Urban format by instead going full metal, and purposely naming the follow-up to Looks Could Kill the confrontational Black Radio Won’t Play This Record, after that very comment was made by an exec at their then-label, Scotti Brothers.

“We may have been a little bit too belligerent about our music,” Doc laughs. “Because we weren’t about to change. We felt that God gave us this chemistry with these six people that we had in our band, and we were doing just fine. We were writing and playing and —”

“—having a great time … and the bureaucracy got in the way,” Joyce says.

Not only did Mother’s Finest have to scratch and claw its way to get to where it is after well over a half-century together, they did it while being led by a powerful Black woman. Joyce ‘Baby Jean’ Kennedy joins the ranks of Tina Turner, Chaka Khan, Merry Clayton, Poly Styrene, Nona Hendryx, and others on the very short list of ‘70s female Black rock singers in a white male-dominated field. Narrow that list down even further to Black women who fronted rock bands at the height of the rock era, and Joyce stands out even more - arguably on her own. (By the way, the fact that I’m listing them illustrates that they’re the exceptions that prove the rule.) In the years since, everyone from Brittany Howard (Alabama Shakes) to Skunk Anasie has thankfully expanded the definition of Black women who rock.

Too Late To Turn Back Now

Mother’s Finest is still out there packing venues at home and abroad. Joyce, Doc, Wyzard, and Mo, backed by Dion Derek, and guitarist John "Red Devil" Hayes who’s been touring with them for over 30 years. In addition to Jamie Foxx and Mary J. Blige’s treatment of “Love Changes,” Labelle recorded a version of “Truth’ll Set Your Free” for their 2008 reunion album. And after all these years, MF’s impact remains, and it’s worldwide.

“We play the Netherlands quite a bit,” Doc says. “And they loooove ‘Baby Love.’ Every time somebody covers it over there, they send it to us. Now they’re even Tik-Toking it!”

“There’s a class in the Scandinavian countries where they teach rock-funk [modeled on] Mother’s Finest,” Joyce says. “Then they had a string section out of Sweden that made a string arrangement of ‘Baby Love.’ It’s the most beautiful thing you’ve ever heard.”

“No vocals, either,” Doc adds.

“Wyzard’s head got really big when he heard that because he wrote the song,” Joyce laughs. “He walked around like, ‘I’m the shit!’ after that.”

Werman would go on to multiplatinum success while helping define the 1980s hard rock sound by producing albums from Mötley Crüe (Shout at the Devil, Theatre of Pain, Girls Girls Girls), Twisted Sister (Stay Hungry), Poison (Open Up and Say…Ahh!), Dokken (Tooth and Nail), and others. Back when he was producing Mother’s Finest, Werman had success with Cheap Trick (In Color, Heaven Tonight, Dream Police), Molly Hatchet (Molly Hatchet, Flirtin’ With Disaster), and Nugent (Free For All, Cat Scratch Fever). In fact, Mother’s Finest was the only band that didn’t see the same level of success his other clients had.

“I absolutely blame the record label,” Werman says now. “Because I had a lot of hits. I would have bet the house on Mother's Finest. They were just insane. I mean, they were groundbreaking, they were excellent. They were explosive. They were enthusiastic. They were cooperative. There was nothing they weren’t.” Werman pauses and considers his words. “I should have been, you know, banging on a table at the label, asking, ‘What's wrong with you people? What are you doing?’”

Asked how they would’ve responded, Werman confesses, “I don’t know. They didn't know how to market it. That's what they said, and apparently they didn't. I was just never able to light a fire for them at the label, and I’ve always just felt bad about it. I’m still pissed off about it. Heartbroken.”

Despite the missed opportunities or the should’ve/could’ve-beens over the last 50-55 years, Joyce’s outlook is bright. “We don't have any regrets, brother,” she says. “I tell you, we’re having a great time. We’re still selling out in Europe every time we go. So whatever it is we’re doing, there are people that get it. Not everybody does but that’s OK because we’re fine, baby.”

Doc laughs, adding, “And it’s too late to turn back now.”

Click here for the full Rockpalast concert from 1978.

Mother’s Finest is still on the road. Check out where they’re playing next here.

Tom Werman’s memoir, Turn It Up!: My Time Making Hit Records in the Glory Days of Rock Music, is available for purchase here.

I saw Mother's Finest open for The Who in 1976, at the 17k-seat Seattle Coliseum. I remember them kicking ass and the crowd being pretty much indifferent. . .

Great post Michael, it's so interesting to learn about the band's history (I had no idea they've gone on for so long) and Tom Werman's recollections in particular. No question racism and misogyny kept them from going as far as they should have - a shame. Nice to be reminded of their music.

I really enjoyed this post and can't think of another extensive article I have read on Mother's Finest. Thank you!

As you point out, there were plenty of other black bands rockin', but maybe MF lacked the heavy funk of the Bar-Kays, Funkadelic, and Isley's (even the Meters were rockin' hard by '72)? Also, as they were a multiracial band, I wonder if that too got in their way? Both Sly and Jimi had pushback from the Panthers for it; I wonder if MF did too. Nevertheless, I love that they stood strong, believed in what they were doing, and never gave in. Their success in Europe was America's loss. Very cool band, and an insightful read. Cheers!