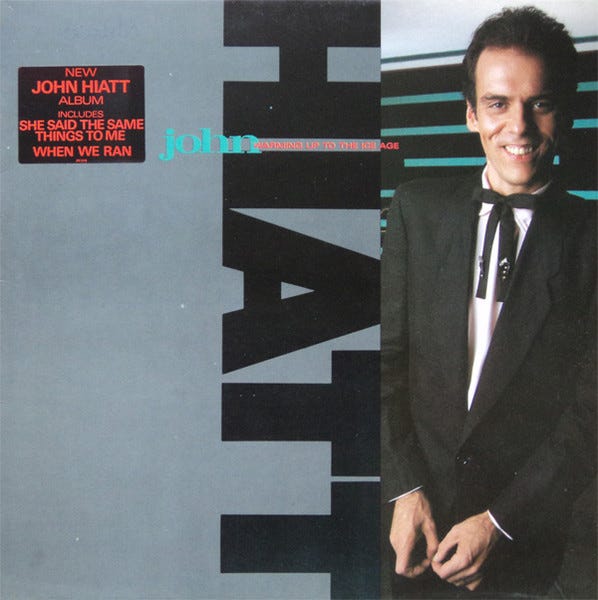

'Warming up to the Ice Age' at 40

Released during the bitter cold month of January in 1985, the icy digital presentation of John Hiatt's last album before sobriety revealed an artist hitting rock bottom in real time.

What follows in an excerpt from “Adios to California,” Chapter 9 of Have A Little Faith: The John Hiatt Story. You can pick up a copy here or wherever you buy books, although I urge you to support your local bookstore whenever possible.

Riding With the King is the album most representative of where Hiatt would be headed musically over the rest of his career. At the time, however, critics were lukewarm at best, with David Fricke stating in his three-star review for Rolling Stone that it was “a good two-EP set conveniently pressed onto one disc.” Listening back now, it’s easy to see the progression from Riding with the King to Bring the Family, which makes the sound of the album in between, Warming up to the Ice Age, all the more puzzling.

The problem is not the songs or the performances, which are both stellar (save for a touch too much mid-’80s-style slap bass); it’s the production. The fact that the production was handled by one of John’s heroes, legendary first-generation Muscle Shoals session man turned bassist for Area Code 615 turned producer and one of the reasons he moved to Nashville in the first place fifteen years earlier, Norbert Putnam, made it even more puzzling.

“I don’t know what we were trying to do,” Putnam admits now. “We were trying to fit that record into the sound of the early ’80s. I don’t know if that was a good thing or a bad thing. I had known John for such a long time on and off, and when we finally made a record together, I thought he was great on it. He played a lot of great rock guitar.” It was a bare-bones band assembled for Ice Age, save for a handful of guests. The guitars were mainly handled by Hiatt with Jon Goin and fellow 615’er Mac Gayden contributing on a couple of tracks. “John wrote such interesting melodies and chord progressions,” Putnam continued. “[The band] was basically John on guitar with Larrie Londin, Nashville’s greatest drummer; Jesse Boyce, one of the hottest bass players I’ve ever heard, he was [like having our own] James Jamerson and more; and my friend Randy McCormick, another Muscle Shoals guy, played keyboards.”

The album kicks off with “The Usual,” later covered by Bob Dylan for the soundtrack to the less-than-stellar 1987 movie, Hearts of Fire. In it, Dylan plays an aging rock star whose female protege (played by Fiona Flanagan) is caught between Dylan’s character (who goes by the generic working-class rocker name, Billy Parker) and a “hot young rocker” (played by Rupert Everett). It had been reported that Dylan had promised to write about a half-dozen songs for the film. In a press conference arranged around the time of the film’s shooting, however, Dylan revealed that he hadn’t written any of them, although the recording sessions for the film’s soundtrack were set to begin in less than two weeks. When it came time for recording, only two songs had been written: “Had a Dream About You, Baby” and “Night After Night.” To pad out his contributions, he looked to other writers.

Fred Koller recalls a moment around that time that possibly sheds some light on Dylan’s process in writing and/or picking songs for the film. “Before Bob went in the studio,” Koller explains, “Mary Martin of CBS took Dylan to Shel Silverstein’s houseboat, to Peter Rowan’s, and a couple of other places. Bob played them various versions of all these songs just to get people’s opinions.”

As luck would have it, at the time Dylan was reportedly dating Geffen A&R executive Carole Childs, who represented John. “That was through Carole,” John recalls. “They were an item at the time. And God bless her. She had him call me, or I called him—I can’t remember which—but I spoke to him on the phone.” Dylan wanted some material for the film, so Hiatt wrote three “basically really bad Bob Dylan songs. That’s what I could come up with, and he wisely recorded none of them.”

Instead, Dylan cut “The Usual” from Ice Age, a song Clinton Heylin designated in his Dylan biography Behind the Shades as “the only redeeming tune from the Hearts of Fire soundtrack.”

For John Hiatt, it was bittersweet. On one hand, one of the greatest songwriters of the twentieth century had recorded one of his songs—a song he had recorded at one of the lowest points in his life, which made Dylan covering it all the sweeter—while on the other, it was recorded during one of the lowest points in Dylan’s career and featured in a movie that almost no one saw.

To this day, the only way to get a copy of Dylan’s version of “The Usual” is to find a used copy of the Hearts of Fire soundtrack or watch his performance of it in the film by searching for it on sites such as YouTube.

If you look past the ’80s sheen, the rest of Ice Age plays as a sturdy southern soul album with some hard rock touches. Parts of it wouldn’t sound too out of place on Malaco, the Jackson, Mississippi soul and blues label that was home to the likes of Johnnie Taylor, Z. Z. Hill, Mel Waiters, Denise LaSalle, and Little Milton, among others. Especially songs like “She Said the Same Things to Me,” Hiatt’s duet with soul belter Frieda Woody. It rolls along on a steady, shaggable groove that fits perfectly into the southern soul subgenre of Carolina beach music, which has its roots, coincidentally (or not), in vocal groups such as the Drifters and the Tams, a group Putnam played bass for while still in Muscle Shoals. “Yeah,” Norbert quips. “Most of that ‘beach’ music was recorded on the Tennessee River, covered in gravel.”

“When We Ran” is one of John’s most moving ballads, pointing the way to future classics that would populate latter-day albums from Slow Turning to Walk On and beyond. And for what seemed like an inevitable pairing, Elvis Costello lent his vocals in a duet of the Spinners’ track, “Living a Little, Laughing a Little.”

“I met Elvis in Nashville at a French restaurant,” Putnam recalls. “He had come to town to work with Billy Sherrill. I couldn’t figure out why in the hell he wanted to come to Nashville and do country. I think he just wanted to know what it’s all about. But Hiatt said he’d be great on this old Spinners song. I wasn’t so sure. I thought he’d had a lot of trouble with Sherrill. So he came to the studio in L.A. and said, ‘I’ve listened to that Spinners song. Do you want to do it pretty much like that?’ So we played the track, and the two of them sang it perfectly together the first time.” The result is probably the most modern-sounding (by 1985 standards) R&B track either artist ever recorded (complete with an over-the-top, Neal Schon–worthy, metallic guitar solo from Goin).

“I don’t remember making Warming Up to the Ice Age,” John admits now. “I remember Larrie Londin, and I remember Norbert being very kind and reassuring, but I don’t remember much else about it. I was just a mess.”

“We got down to the end of it,” Putnam recalls. “We’re starting to mix, and he called me on a Monday morning. He said, ‘I’m not feeling well.’ I said, ‘What happened?’” Friday night on the way home after the session, John was arrested for drunk driving and had to spend forty-eight hours in the Franklin jail.

“Getting arrested was the turning point in his life,” Putnam continues. “He quit drinking. You know, a true alcoholic, they drink to be normal. He made that record, and he was great on it, but he said, ‘Norbert, I was drinking a quart a day, and you never knew.’ And I didn’t know. There just wasn’t any indication. He certainly never appeared inebriated in any sense. So he took a vow that he wouldn’t drink again.”

He broke that vow.

Jail may have fired a warning shot, but he wasn’t ready to call it quits. When you ask an addict about his particular rock bottom, it’s not always clear-cut. They all have their own process. Sometimes it’s spiritual; sometimes it’s a legal matter that snaps them out of it. For John, it was a drive through the Deep South in the company of a Dutch woman.

“I remember thinking the way I could solve my problems,” he explains. “This marriage that wasn’t working and having this baby—this is the clearest alcoholic thinking that an alcoholic can do—I thought, I know what I’ll do. I’ll bring over this girlfriend that I’ve been carrying on with over in Holland when I was touring over there. This was my solution to my problems. So I flew her over—we’d finished making Warming Up to the Ice Age—and I picked her up at the airport in Nashville. I rented a 1984 black Camaro. I got a quarter ounce of cocaine from a buddy. I had a cooler, and I stocked it with beer, and of course I kept the vodka on ice as well, and I proceeded to show her the South. We went to Gulfport, Mississippi. I took her down to New Orleans to show her the sights—which were mainly just the bars—driving what I now refer to as my death-black 1984 Camaro, and it stopped working. I couldn’t get high. All of a sudden, I started crying, and I couldn’t stop crying. I mean for days. Driving and crying—thank you, fellas—and she was there with me. And I know she was like, ‘What the hell have I gotten myself into?’ I finally just couldn’t take it anymore.”

John had seen a psychiatrist the previous year who suggested he go into treatment. At two o’clock in the morning, somewhere deep in Mississippi, he pulled the Deathmobile over at a gas station. “Bright lights and bugs everywhere,” he recalls. “There was a little phone booth. I called my still-wife in Los Angeles and said, ‘I’m coming home. I’m going to treatment.’ And that was the beginning of the end. I dropped this gal off in Nashville, turned in the rental car, and flew home to L.A. on August 5th.” The very next day, John Hiatt entered treatment in Pasadena, California. “That was my first day sober: August 6, 1984.”

When John got out of treatment, the real work began. “I had destroyed practically every aspect of my business career and used up pretty much everything,” he admits. “But somehow I still had insurance, which paid for the treatments. When I got out, my wife and I . . . we decided . . . I just couldn’t move back in with her. It wasn’t gonna work. We were estranged, in other words.”

While he was in treatment, John had met a guy who had an apartment over his garage that was available to rent. “So once I got out of treatment, I just moved into this little garage apartment. And the first six months of my sobriety, all I did was hang around other recovering people and ask for help and direction. I remember I ate doughnuts by the dozen because I had sugar cravings, and I read a lot of Mark Twain. The first one I picked up was A Pen Warmed-Up in Hell, which was perfect reading,” he laughs. “So that was my first six months of sobriety.”

Warming up to the Ice Age was finally released in January 1985, right in the middle of John’s fragile first few months of recovery. He was still living in Pasadena, unable and unavailable to do all the things needed of an artist to promote a new album, but his label didn’t necessarily step up to the plate during his recovery. “I couldn’t get Geffen to promote the record,” Putnam recalls. The failure of Warming up to the Ice Age came down, of course, to business. By now for John, it had become a familiar tune.

“The record labels in those days probably had five new album releases every month,” Putnam continues. “They were only going to promote one of those records; four of them were going to die a quick death. I would say Geffen was a smaller label, and my chances were better with them than they were with the big labels like when Clive Davis was running Columbia. He was putting out ten albums a month, but he’s only promoting one of them. And if it doesn’t get promoted, you’re not on the radio. The thing about Hiatt’s career is that I don’t think any of the labels ever really promoted John the way they should have.”

Although his career was once again at stake, this time, John had more important things to worry about. He was deciding how he was going to live the rest of his life. And he had decided to live it sober.

Thanks for reading. For the full story, pick up a copy of Have A Little Faith: The John Hiatt Story wherever you buy books.

Sobriety perhaps collided with karma but whatever took place from that point on Hiatt's music/songwriting to me was as good as it gets for several albums and decades and once again, thank you, this time for taking us through those dark moments.

I became a Hiatt fan with “Bring the Family” and “Slow Turning”. I have heard most of what he has done since and ignorant to anything before. “The Usual” is great. Thanks for sharing the chapter. Looking forward to reading the book!