When New York Had Her Heart Broke

John Hiatt and the "9/11 song" he didn't want to record.

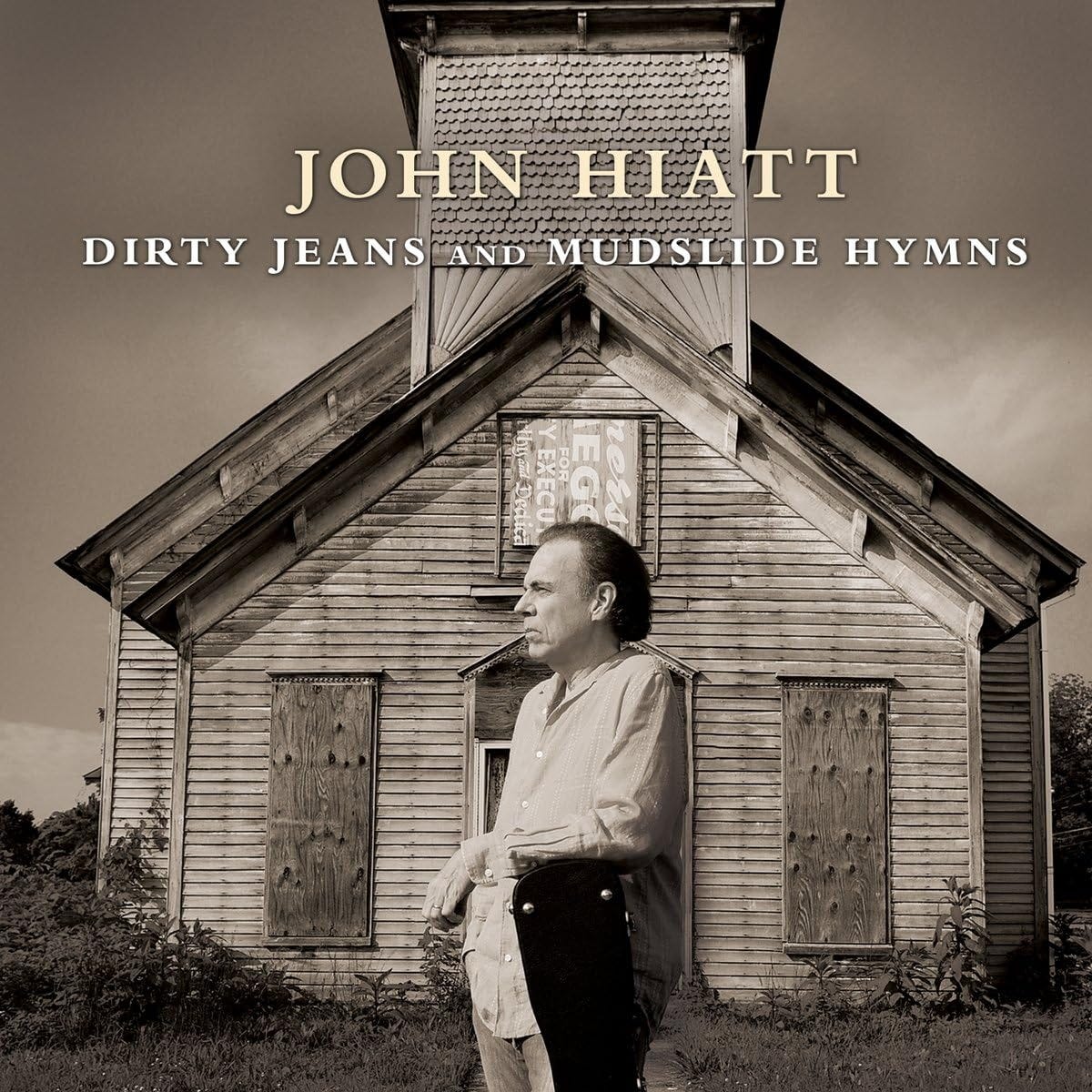

What follows is an excerpt from Chapter 18, “The Caveman Cometh,” of Have a Little Faith: The John Hiatt Story. It details the recording of the last track on Hiatt’s 2011 album, Dirty Jeans and Mudslide Hymns, “When New York Had Her Heart Broke.” Included here are interview excerpts from producer Kevin “Caveman” Shirley, guitarist Doug Lancio, and Hiatt.

But first, an excerpt from Chapter 16, “Crossing Muddy Waters,” that details Hiatt and the Goners’ experience in NYC on 9/11/01.

Interestingly, The Tiki Bar Is Open was his second and last album for Vanguard and was released on Tuesday, September 11, 2001, along with Bob Dylan’s Love and Theft. As it turns out, Hiatt and the Goners were in New York City on that day.

“We were on the B. B. King blues tour,” John explains. “We’d had an offer to do a television show. So we came into the city, brought all the equipment in, and the bus had to go back out to New Jersey to park, but we stayed in the city up around Thirty-Third and Lex, somewhere in there. That next morning, I was awakened to a phone call from my wife. ‘Where are you?’ ‘I’m in New York City.’ And she said, ‘Turn on the TV.’ As I turned it on, the second plane flew into the second tower. I called the other guys, and we all got out of the hotel, went out on the street, and there was nobody in the street. I guess they told people not to come to work. They were already clearing the areas in Manhattan. It was eerie. It was creepy. We walked up Central Park, just trying to get a grip on things. F-15s were circling Central Park. It was like a scene out of Star Wars.

“We got out of the city. My road manager at the time, Nineyear Wooldridge, got probably the last van available for rent in the city. Our crew guys got the equipment loaded from the place where it was and drove the van over to the bus in New Jersey. We walked down to Penn Station and caught the train to Philly where the bus met us. But I remember the train rounded the tip of Manhattan right where that happened, and the people on the train were weeping. Just weeping. It was overwhelming.”

In the context and in the shadow of a national tragedy, the largest terrorist attack on American soil since the bombing of Pearl Harbor almost sixty years earlier, hearing that the tiki bar was open was as comforting for listeners as it probably was for John when he was inspired to write it; it meant that New York City was still there, that America was still here, and ultimately, we’d survive.

Chapter 18 excerpt:

Kevin Shirley recalls, “John had this little song, and it was almost like a haiku, these little two-line rhyming couplets that he had. He was running through his demos; he had about seventy songs, and he played me that one. I said, ‘I’d like to do that one,’ and he said, ‘No, I don’t want to do a 9/11 song.’ He said, ‘Every fucking Tom, Dick, and Harry has some 9/11 song.’ So I said, ‘I don’t think that should be your benchmark as to why you do it or don’t. But anyway, you don’t want to do it, so we’ll move along.’ So we moved on.

“Everybody was coming out with stuff,” John explains. “There was a lot of gratuitous monkey business going on. And I just didn’t want to stink it up by giving people something else they didn’t really need. Everybody was suffering, and most of all New York City itself, which is why I wrote a song specifically about New York.”

Still, it had been ten years, so the Caveman persisted. “I guess we’d done ten or eleven songs,” Kevin says. “And John said, ‘What do you want to do next?’ I said, ‘Man, I just keep coming back to that “When New York Had Her Heart Broke” song,’ and he was like, ‘No, I don’t do that song, man. I really don’t want to do that song.’ And I said, ‘If you would just trust me, let’s just do the song. If it doesn’t work, we just won’t do anything with it. But I’d just like to try and just do something really different.’

“I wanted to have chaos around the simplicity of the acoustic guitar and his famous poetry,” Kevin continues. “I had the guys go in the studio, and I wanted them to play anything and everything, but with no relation to anything. I remember the bass player (Patrick O’Hearn) was playing something, and he couldn’t quite get his head around it. I walked into the studio while they were playing, and I pulled his headphones off of his head, and I turned up the fuzz on the bass guitar. And I said, ‘Just play anything, just keep it in this sort of drone key that we have, but play anything! Don’t worry about time. You guys think too much about where you want to take this.’ So they played it. We did two or three takes of it, and then this one take just came together. Nobody knew what to expect. John had been so resistant to recording the song. Then I played it back, and I tell you, every single one of us was crying. It was like one of those moments. One of the moments in the studio that just doesn’t come along. Kenny (Blevins), the drummer, was crying. The song clearly attached itself to them; you could hear the helicopters, and you could hear the devastation. You could hear all these things if you listen to it, and somehow we could hear them in that mess that surrounds beautiful, simple, acoustic guitar and poetry. It just comes out, almost like coming out of a mist.”

“We never played that song very often,” Doug Lancio explains. “But we were up around New York at one of our gigs [and we] pulled it out. Our sound guy had a video somebody had put together; it might even have been him, but it was just all these 9/11 images. It was still very fresh. It was one show where he had access to this huge video screen behind us. So he got the files that he needed, and when we played that song, he played the video behind us. I wasn’t sure what was going on, but I just saw everybody in the crowd crying. It really was quite a moment.” Kevin Shirley sums up the reception to “When New York Had Her Heart Broke.” “For a song that wasn’t going to make the record, it made a huge dent on all sorts of people.”

Inspiring story and beautiful song. I looked up the lyrics:

On that fiery day when the towers gave way

New York had her heart broke

New York had her heart broke

Many heroes died trying to save someone inside

When New York had her heart broke

New York had her heart broke

And I was there that day

And I don't know what to say

'Cept New York had her heart broke

New York had her heart broke

And the day that felt dark, F-16's over Central Park

When New York had her heart broke

We were dazed out in the street

From the blood and dust and heat

When New York had her heart broke

New York had her heart broke

And the world changed that day

Forever some men say

When New York had her heart broke

In a million years she couldn't cry more tears

New York had her heart broke

New York had her heart broke

Oh, but she will rise again

===================

Exquisite in its simplicity! Thanks for highlighting it.