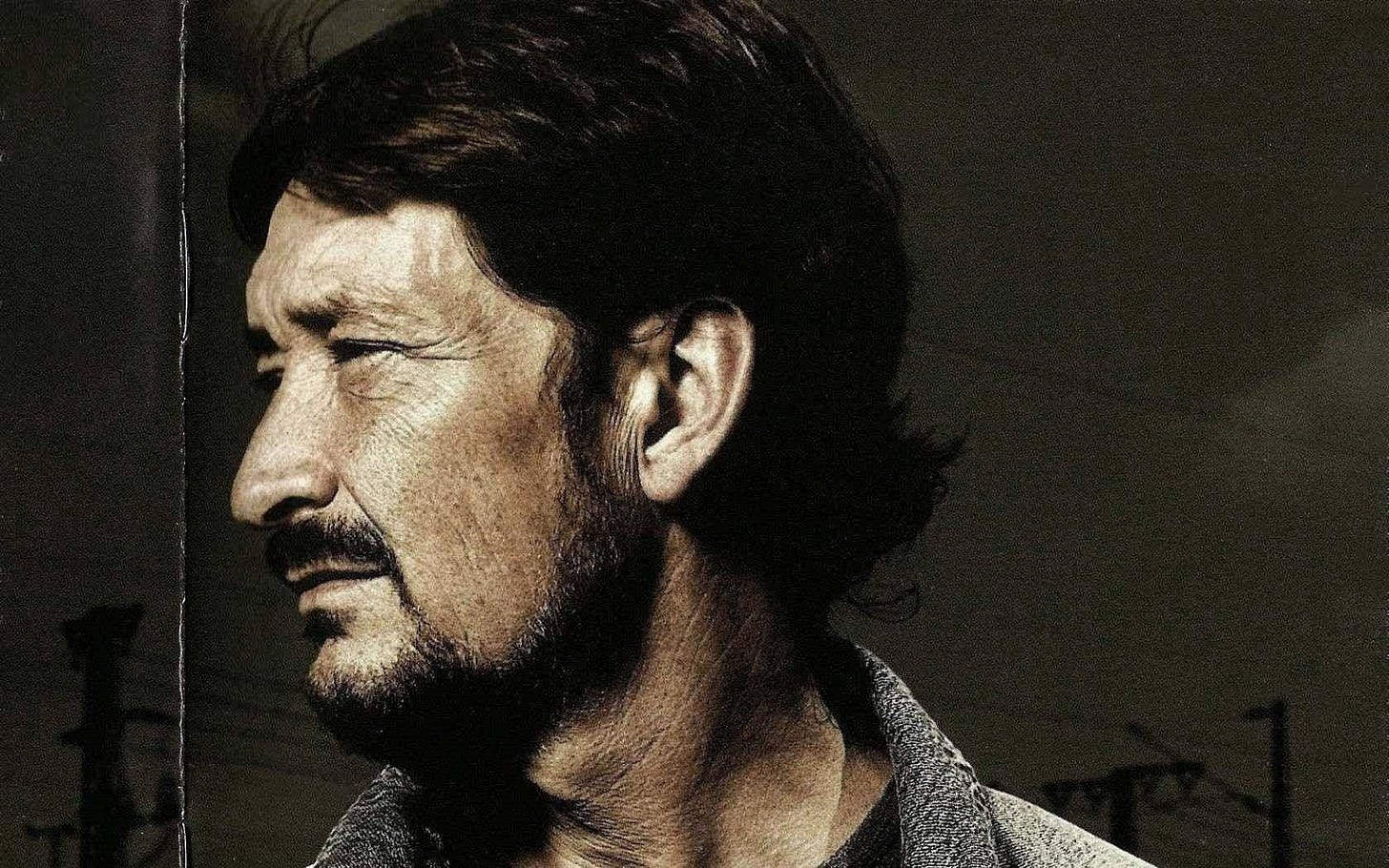

Tell Me There's a Heaven: Remembering Chris Rea

Remembering a superb guitarist and vocalist who could wring the blues out of a slick pop tune.

I was hoping we could make it out of 2025 without losing another musician who profoundly impacted many of us, but unfortunately, here we are.

It was probably around 1988 and on WZZU-FM, 94-Z in Raleigh, NC, where I was first exposed to “Workin’ On It” by Chris Rea. To this day, I believe it was the only time I’ve heard him on the air other than his 1978 hit, “Fool (If You Think It’s Over)” or his seasonal classic, “Driving Home for Christmas” (that made it onto this year’s Christmas Mixtape). I found a cassette of New Light Through Old Windows soon after. I didn’t realize until later that it was a compilation. It played like a cohesive album, and it made me a lifelong fan.

At first glance, Chris Rea could be hard to pin down. “Fool (If You Think It’s Over)” is straight-up Adult Contemporary verging on the retro-fitted tag of Yacht Rock, while “Workin’ On It” fits squarely into the blues-rock world. But Rea was much more. He embodied a calm, cool demeanor both on record and in concert. While his slide playing was tasteful—but could also bite and sting when needed in the true Lowell George tradition—his voice was his true gift. While he didn’t have the pipes of, say, Paul Rodgers, Steve Marriott, Rod Stewart, or Frankie Miller, his expressive phrasing was immaculate, and his vocal tone was deep and comforting, even when it was delivering lyrics of unimaginable sadness. (Rodgers covered Rea’s “Stone” on the only album by The Law, Rodgers’s collab with Faces/Who drummer Kenney Jones in 1991. Rea contributed guitar on the track.)

Rea was the artist who most opened my mind to how the blues could successfully be incorporated into a pop framework. Although artists such as Boz Scaggs and Eric Clapton had moved back and forth between pop, rock, and blues over the years, it was usually at the expense of one or two of those styles over the other. Rea could craft a tune with a pop sensibility while still injecting it with a blues feel. No matter the backdrop—even the goofiest period-precise electronic drums were no match—his guitar and vocals kept the proceedings relatively swampy. Nowhere was this more apparent than on the title cut to 1989’s The Road to Hell.

A kinda-sorta concept album, The Road to Hell is probably the best place to get on board with Rea. It’s where that warm, soothing voice guides you through a world that’s turned into a cynical hellscape of crime and consumerism, but he offers hope despite it. The album romanticizes America through the eyes and ears of an Englishman. (Rea hails from a port town in the Borough of Middlesbrough in North Yorkshire.) His character believes the “big long roads” in “Texas” offer solace from the “evil” he sees on his TV, so he and his family jump in the car and go “Looking for a Rainbow.” All the while, he can feel safe in his lover’s “Warm and Tender Love” while fantasizing about the joy found in “Daytona.” (Rea was a serious motorhead).

Auberge, The Road to Hell’s follow-up in 1991, although not as thematically consistent as its predecessor, sonically offered more of the same.

Rea, during this era, occupied a similar sonic space as Mark Knopfler and even what Tony Joe White was releasing at the time. While working on my Swamp Rock book, I planned to include him in the chapter that details the swamp sound that couldn’t completely be hidden under the slick production of the late ‘80s and early ‘90s (unfortunately, I just couldn’t find the space). When you listen to songs like Rea’s “Curse of the Traveler” alongside, say, Tony Joe White’s “Cold Fingers,” they both have the same moody, nocturnal, elusive, journeyman vibe.

Frustratingly, Rea never really broke through in the States aside from “Fool” and “Driving Home for Christmas,” but his albums were consistently strong. His breezy, laid-back productions fit well thematically into the summer season. So much so that by 2000, he released a comp called King of the Beach.

That same year, Rea was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, ultimately losing his pancreas, duodenum1, and gall bladder. In 2001, he underwent what’s called a “Whipple” procedure. Also called a pancreaticoduodenectomy, the Mayo Clinic describes it as, “An operation to treat tumors and other conditions in the pancreas, small intestine and bile ducts. It involves removing the head of the pancreas, the first part of the small intestine, the gallbladder, and the bile duct.”2

Rea told the local press in North England in 2008, “It’s a twelve-and-a-half-hour operation, and it takes you a year after to see if you will even recover from it. The two guys who went in with me to have it didn’t get through.”

While in recovery, he gained a new perspective. “It’s not until you become seriously ill and you nearly die and you’re at home for six months that you suddenly stop and realise that this isn’t the way I intended it to be in the beginning,” he explained. “Everything that you’ve done falls away, and you start wondering why you went through all that rock business stuff. Now I don’t look any further forward than today; I really do live day to day. What my health problems have given me is constant optimism. If it rains, I say great rain is nice.”3

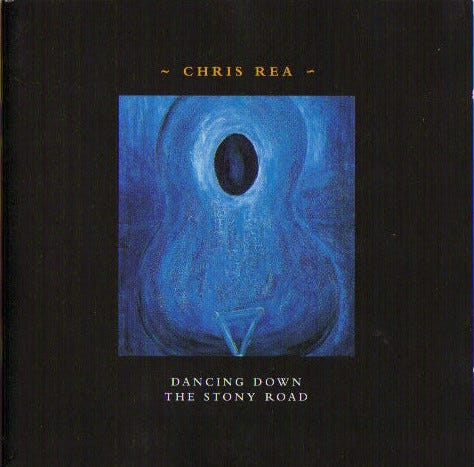

After receiving a copy of Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue and listening to the music of artists like Sister Rosetta Tharpe during his recovery, he had an epiphany. He wanted to make music that reflected the pain he felt during his illness, while emphasizing the resilience of making it through. He dove even deeper into the blues, shedding the slick productions of the past in favor of pure, raw emotion.

The result was Dancing Down the Stony Road, a double album that, for me, stands as his masterpiece. While it was resequenced and condensed to a single disc in the US (called just Stony Road), the full original UK version is the one to seek out. It’s one of the great personal statements released this century so far, as it details his journey of recovery as well as the beginning of his exploration of the blues—a sonic pilgrimage to the Delta taken by many before him, from Jagger and Richards to John Fogerty—but done through the eyes of someone who's realized the fragility and beauty of life.

Rea’s 2005 effort was even more ambitious. Inspired by his deep dive into the Delta, he released Blue Guitars, an 11-disc, 130-song album of all-new original material that touched on every style of blues he could imagine.

Rea continued releasing new music into the 2010s (including Road Songs for Lovers in 2017). And “Driving Home for Christmas,” I’m sure, gave him a decent check he could count on at least once a year.

He died on December 22, 2025, and his family released this statement:

It is with great sadness that we announce the passing of our beloved Chris, who died peacefully earlier today following a short illness.

Chris’s music has created the soundtrack to many lives, and his legacy will live on through the songs he leaves behind.

Chris Rea was not a one-(or two) hit wonder. He was someone who was always searching, always playing, always digging deep into what inspired him. He was perpetually curious, and diving into his discography is an endlessly rewarding experience. Here’s just a sample of some of my favorites, but I encourage you to find your own—something that can get you dancing down the road, no matter how many stones there may be in your passway.

Apple Music listeners can access this Mixtape here.

The first part of the small intestine, just beyond the stomach.

https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/whipple-procedure/about/pac-20385054

https://archive.ph/20150405195527/http://ne4me.dev.visualsoft.co.uk/celebrities-3/middlesbrough-superstar-speaks-exclusively-12.html#selection-343.0-351.178

I too discovered Chris through “new light..”. I was a kid at the time. Then it was Auberge, when I worked at a record store and we had a promo copy. I appreciate you mentioning Knopfler and Lowell George, the later of which I adored but failed to make that connection. It is surprising to me he never found success in the States in a similar fashion as these contemporaries.

Great post. It’s sent me searching for the Stony Road album.